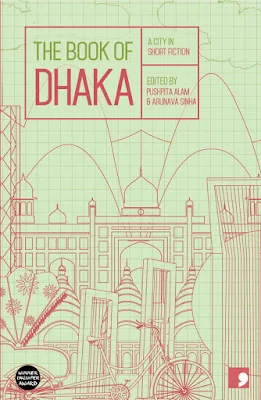

১.৮ কোটি মানুষের বাসস্থান হচ্ছে বিশ্বের দশম বৃহত্তর শহর আমাদের ঢাকা। কমনওয়েলথ ফাউন্ডেশন ও আর্টস কাউন্সিল ইংল্যান্ডের যৌথ উদ্যোগে এই ঢাকা শহরের কিছু ছোটগল্পের ইংরেজি অনুবাদ নিয়ে বই প্রকাশ করেছে যার নাম 'দ্য বুক অফ ঢাকাঃ এ সিটি ইন শর্ট ফিকশন। বইটি ইতিমধ্যে ইংল্যান্ডের সাহিত্যিক সমাজে বেশ নজর কাড়তে পেরেছে। বইটি পুরস্কৃত হয়েছে ইংলিশ পেন অ্যাওয়ার্ড এ। বইটির সূচি প্রশংসনীয়।

The Raincoat - Akhteruzzaman Elias

The Weapon - Syed Manzoorul Islam

The Decision - Parvez Hossain

Mother - Rashida Sultana

The Circle - Moinul Ahsan Saber

Home - Shaheen Akhtar

The Princess and the Father - Bipradash Barua

Helal was on his Way to Meet Reshma - Anwara Syed Haq

The Path of Poribibi - Salma Bani

The Widening Gyre - Wasi Ahmed

গল্পগুলি অনুবাদ করেছেন Pushpita Alam, Arunava Sinha, Syeda Nur-E-Royhan, Masrufa Ayesha Nusrat, Arifa Ghani Rahman, Mohammad Shafiqul Islam, Marzia Rahman, Mohammad Mahmudul Haque, Ahmed Ahsanuzzaman.

এই বইয়ের একটি গল্প আমি পাঠকদের জন্য তুলে দিচ্ছি। আশাকরি গল্পটি পড়বেন, এবং বুঝতে পারবেন ছোটগল্প রচনায় আমাদের দেশের গল্পকারেরা কত শক্তিমান।

বইটি আমাজনে কিনতে হলে এইখানে ক্লিক করুন।

ঢাকায় প্রথমার দোকানে, পাঠক সমাবেশে খোজ করুন।

বৃত্ত

মঈনুল আহসান সাবের

মশারির একদিক উঠিয়ে ফিরোজা নেমে গেছে ভোর হওয়ার সঙ্গে-সঙ্গে। নেমে যাওয়ার আগে তাকে একবার ঠেলেছিল আলমের খেয়াল আছে। তার ঘুম ভাঙাল দুটাে চড়ুই পাখি। রোদ পুরো জানালা গলিয়ে এসেছে ঘরের ভেতর। রোদ পড়ায় ময়লা মশারির একাংশ অতি উজ্জ্বল। চড়ুই, পাখি দু’টাে থেকে চােখ সরিয়ে সেদিকে কতক্ষণ তাকিয়ে থাকে সে। ছেলে দু’টাে পড়ছে বারান্দায় বসে। মশারির মধ্যে উঠে বসতে-বসতে সে বারান্দায় বড়টির মাথা সামনে-পেছনে দুলছে দেখতে পায়। শরীরের আড়মোড়া ভাঙতে সে অনেক সময় নেয়। সারাটা দিনের মধ্যে এই সামান্যক্ষণটুকুই আনন্দের। এইটুকু সময় সে নিজের ইচ্ছেমতো ফুরাতে চায়। একবার বিছানা ছেড়ে ওঠার পর আর কোনও ফুরসৎ নেই। বিছানা ছেড়ে সামনের দেয়ালে বাধানো ছোট স্নান আয়নায় নিজেকে দেখে একপলক । কোনও দুঃখ ঘাই খেয়ে ওঠার আগেই সে চোখ সরিয়ে নেয়। কিন্তু ওই একপলকের মধ্যেই অনেক কিছু ধরা পড়ে গেছে। দু'চােখের নীচে কালি, গাল ভেঙে গেছে, ছেড়া ময়লা গেঞ্জি । আয়নার সামনে দাঁড়িয়ে মাথা নীচু করে ব্ৰাশে পেস্ট নিতে-নিতে সে আপন মনে হাসে।

রান্নাঘরের পাশে কলতলায় বসার সময় ফিরোজা তাকে একপলক দেখে। আলম তাকে বড় ভালোবাসে। বিয়ের পর দশবছর ধরে শুধু ক্লান্তি বেড়েছে, ভালোবাসার অনেক কিছুই সে ফিরোজাকে দেখাতে পারেনি। কলতলা এই গ্ৰীষ্মের দিনেও কাদায় একাকার। কোথাও কালচে শ্যাওলা প্রায় জমে উঠেছে। ক্ষয়ে যাওয়া দেয়ালে নোনা আস্তর; ফেটে যাওয়া সিমেন্ট বাধাইয়ের ফাঁক-ফোকর গলে বেরিয়ে এসেছে চারাগাছ। আরও একটু সামনে বেশ বড় একটা গাছ। কলতলায় বসলে সেই গাছের কালো-কঠিন গুড়ি পর্যন্ত নজর চলে। আলম এসব দেখতে-দেখতে মুখ ধুয়ে নিল। ততক্ষণে ফিরোজার নাস্তা তৈরি শেষ। আটার রুটির সঙ্গে ভাজি কিংবা গুড়, গতরাতের তরকারি থাকলে তার কিছু। পেছনের বারান্দায় যে-দিকটায় সকালের রোদ এসে পড়েছে সেখানে পুরনাে একটা ছােট টেবিল। তারা চারজন কোনওমতে বসে। কতকিছু আলগা হয়ে গেছে দশ বছরের অভাবের সংসারে । কিন্তু এই দীর্ঘদিনেও নিয়মটা ভাঙেনি আলম, এসময় ফিরোজা তার পাশে বসবেই। নাস্তার এই সামান্য সময়টুকুয় ক্ষণিকের জন্যে হলেও একটা বন্ধন গড়ে ওঠে। আর ফিরোজা পারেও বটে। একটু পরেই কাজের চাপ বেড়ে যাবে তাই এই সময়টুকু মাতিয়ে রাখে সে। নোটন-টােটনকে নাস্তা এগিয়ে দিয়ে সে আলমকে বলল-আজকে অফিসে যাওয়ার আগে তোমার কী-কী কাজ, জানো? আলম খুব গম্ভীর হয়ে মাথা নাড়ে, না তো। তবে শোনো ফিরোজা আঙুল ওঠায়, এক, বাজারে যেতে হবে, দুই, রেশন আনতে হবে, তিন, নোটন-টােটনকে স্কুলে পৌঁছে দিতে হবে । আলম মাথা নোয়ায়, জো হুকুম, হয়ে যাবে। রেশন সপ্তাহে একদিন, বাকি কাজ দুটো রোজাকার। কিন্তু প্ৰায় এইভাবে প্রতিদিন আরম্ভ করে তারা।

নাস্তা শেষ করে বাজারের ব্যাগ হাতে বের হতে-হতেই এই আনন্দের রেশটুকু চলে যায়। পয়সা খরচ করার ক্ষমতা তার কত কম-রোজ এসময় তার মনে পড়ে যায়। বাজার বাড়ির সামান্য দূরে। এটা একটা বড় সুবিধা, নইলে বাজার থেকে ফিরেই তাকে অফিসে ছুটতে হত। অনেক সময় নষ্ট হয় বাজারে । এক জিনিসের দাম বহুবার জিজ্ঞেস করে আবার ঘুরে-ফিরে আসে। কেনার ইচ্ছেটুকু বাদে আর কোনও ক্ষমতা নেই তার—এই চিন্তা খুব ক্ৰোধ জাগিয়ে দেয়। কিন্তু কিছু করার নেই, কম পয়সায় পচা-বাসি জিনিস কিনে সে বাড়ি ফিরে আসে। তখন বসবার সময় নেই। সে বাজারের ব্যাগ নামিয়ে রেখে রেশনের ব্যাগ-কার্ড নিয়ে বেরিয়ে যায়। রেশন দোকানে লম্বা লাইন। তার মতো অনেক অফিসযাত্রীরা লাইনে। এই সামান্য সময়েই লাইনের মধ্যে দ্রব্যমূল্য, রাজনীতি, সামাজিক অবক্ষয় বাদামের খোসার মতো ভেঙে-ভেঙে যায়। তার সময় আসতে দেরি হয়। বাড়ি ফিরে সে গোসল সেরে নেয়। তাড়াতাড়ি। এখনও পৌনে এক ঘণ্টা বাকি অফিসের । বহুদিনের অভ্যেসে সে এসব ব্যাপারে অত্যন্ত অভ্যস্ত। ঘড়ির কাটার সঙ্গে তাল মিলিয়ে এগোয়। অফিসে পৌছতে দেরি হয় না। সে গোসল সেরে বারান্দার তারে কাপড় মেলে দিতে-দিতে দেখে নােটন-টােটন স্কুল-ড্রেস পরে খাবার টেবিলে বসে গেছে। খুব তাড়াতাড়ি খেতেও পারে আলম। ফিরোজা প্রতিদিন বারণ করে--দুটাে মিনিট দেরি হােক অফিসে, এমন কিছু এসে যাবে না, তুমি ভাত মাথায় তুলছ কেন?

ভাত বেড়ে দিতে-দিতে ফিরোজা বলে—তুমি বড় শুকিয়ে গেছ, দিনরাত এত খাটছি। অভাব আর ক্লান্তির নীচে কত ভালোবাসা চাপা পড়ে গেছে, এইসব মুহূর্তে তা ঘাই খেয়ে ওঠে । এ-জন্যেই ফিরোজাকে বড় ভালো লাগে আলমের। খুব একটা ভেবে চিনতে বলেনি হয়তো ফিরোজা, আর এটুকু বলা ছাড়া আর কিছু করার নেই ফিরোজার, কিন্তু আন্তরিকতাটুকু টের পায় আলম। এ-সময় একসঙ্গে খেতে বসে না ফিরোজা। তার অনেক কাজ। চুলোর আগুনে তেতে-যাওয়া-মুখে ভাত বেড়ে খাইয়ে আলম আর নোটন-টোটনকে বিদায় করে সে ঘর গুছাবে, বাকি রান্না সারবে, কাপড় ধোবে, এভাবে তার সারাটা দিন চলে যায়। দুপুরের পর-পর ফিরে আসে নোটন-টােটন, সন্ধ্যার আগে-আগে আলম।

আলমের একটা পুরনাে মোটরসাইকেল আছে। বিয়ের পরপরই ধার করে কিনে ফেলেছিল। এখনও খুব কাজ দিচ্ছে। মোটরসাইকেলটা গত পরশু ওয়ার্কশপে দিয়েছে; আজকাল প্রায় ট্রাবল দেয়। চেনা-জানা ওয়ার্কশপ বলে মাসের মধ্যে দু-তিনবারও অল্প খরচে সারিয়ে নিতে পারে। নোটন-টােটনকে স্কুলে পৌছে দিয়ে সে অফিসে যাবে। দরজায় দাঁড়ানো ফিরোজার কাছ থেকে বিদায় নিয়ে তারা রাস্তায় নামে।

আলম একটা রিকশা নেয়। রিকশা নেয়া তার পোষায় না। কিন্তু মোটরসাইকেল নষ্ট, এই অফিস আওয়ারে বাসের জন্যে দাড়ানো ও অর্থহীন-আলম এইসব ভেবে ব্যাপারটা চুকিয়ে ফেলে।

রিকশা থেকে নেমে ভাড়া চুকিয়ে আলম সেখানেই দাঁড়িয়ে থাকে। নােটন-টােটন স্কুলের গেট পেরিয়ে ভেতরে অদৃশ্য হয়ে গেলে সে ফুটপাতে উঠে এল । এখনও পনের মিনিট বাকি অফিস আরম্ভ হওয়ার । এই সময়ের মধ্যে হেঁটে সে দিব্যি পৌছে যাবে।

অফিসে পাঁচ-দশ মিনিট দেরি হলে কোনও ক্ষতি নেই। কোনও জবাবদিহির সম্মুখীন হওয়ারও ভয় নেই। অন্য অনেকের এ-রকম পাঁচ-দশ মিনিট দেরি হরদমই ঘটছে। অফিস ছুটি হওয়ার আগে বেরিয়ে পড়াও চলে। কিন্তু আলম পারে না। ঠিক সময়ে অফিসে পৌছানো এক শক্ত রুটিনের মতো হয়ে দাঁড়িয়েছে। অত নৈতিকতার ধার ধারে না সে, এ-কথা ঠিক, অফিসে ঠিক সময়মতো না-পৌছলে ফাকি দেয়া হবে এ-কথাও তার মনে আসে না। কিন্তু সময়মতো অফিসে পৌছানোর রুটিনটুকু সে এড়াতে পারে না ।

অফিসে তখন যারা এসেছে তারা নিজেদের চেয়ারে বসে গল্পে ব্যস্ত। আসিফ ছোকড়া অল্পদিন হল পেছনের দরোজা দিয়ে চাকরিতে ঢুকেছে। নিজের দায়-দায়িত্ব ছাড়া কাঁধের ওপর আর কোনও চাপ নেই, তার গলা রোজকার মতো আজকেও জোরাল শোনাচ্ছে। নিজের চেয়ারে বসে রুমালে মুখ মুছে সামান্যক্ষণ কান পাতল সে, আসিফের দেখা গতকালের বিদেশী সিনেমার গল্প। একটু পরেই এ গল্প চাপা পড়ে যাবে সে জানে। রোজকার ব্যাপার। এরপর জিনিসপত্রের দাম, বিশ্ব রাজনীতি, রাস্তা-ঘাট, হাসপাতাল কিংবা যাতায়াত ব্যবস্থার দুরবস্থা, বাসের ভিড়, মুদ্রাস্ফীতি, রিকশাআলাদের অভদ্রতা ক্রমান্বয়ে ঘুরে-ফিরে আসবে।

সারা সকালে জুড়ে কী ক্লান্তি জড় হয়েছে, চেয়ারে শরীর এলিয়ে দিলেই সে টের পায়। ব্যাপারগুলোর একটাও তার পক্ষে এড়ানো সম্ভব নয়। বাজার, রেশন, নোটন-টােটনকে স্কুলে নিয়ে আসা, বাসায় নিয়ে যাওয়া সব তাকেই করতে হবে। কিন্তু এই সামান্য বিশ্রামের সময় ক্লান্তি সারা শরীরে ছড়িয়ে পড়লে সে বুঝতে পারে, কী দ্রুত সে নিজেকে ক্ষয় করে ফেলছে। সামনে রাখা গতকালের অসমাপ্ত ফাইল টেনে নিয়েও সে মন থেকে কথাগুলো ঝেড়ে ফেলতে পারে না। কী দ্রুত ফুরিয়ে যাচ্ছে সময়, তার আগে কী দ্রুত ফুরিয়ে গেছে তার যৌবন। ফিরোজার ভালোবাসাটুকু তাকে ধরে না রাখলে সে সব ছেড়ে এতদিনে হাঁটতে-হাঁটতে সেই কোথায় চলে যেত। এই একঘেয়ে জীবন, মাঝে-মাঝে কী একটা ভীষণ ইচ্ছে করে চিৎকার করে ওঠার। অথচ সে-জন্যে প্রয়োজনীয় সাহস আর শক্তিটুকুও তার নেই। তার আর ফিরোজার সময় পেরিয়ে গেছে, মাত্র দশবছর পরেই এ-রকম মনে হয়, কিন্তু এই চিন্তার মধ্যে বুদ্বুদের মতো জেগে ওঠে দুঃখ-মাত্র দশবছরেই ফুরিয়ে গেলাম! অভাব আর ক্লান্তির খোলস ক্রমশ পুরু হয় আর গায়ের সঙ্গে আরও সেঁটে বসে। খুব একটা ইচ্ছে করে হঠাৎ করে কিছু করে বসার, একটা ভীষণ রকম অনিয়মের। কিন্তু হঠাৎ করে একটা সাধারণ ফ্যামিলি পিকনিক কিংবা একদিন শখ করে বড় হােটেলে খাওয়া-এই আয়াসসাধ্য কাজগুলোও হয়ে ওঠে না। সে টের পায়, এসব তার পক্ষে আর সম্ভব নয়। হঠাৎ করে করে ফেলার সাহসটুকুও যদি তার থাকত!

লানচের সময়টুকুতেও অবসর নেই। নোটন-টােটন স্কুলের গেটে দাঁড়িয়ে থাকবে ছুটির পর । এ-সময় লাঞ্চের পরও দশ-পনের মিনিট নিদ্বিধায় চুরি করে আলম। নোটন-টোেটনকে স্কুল থেকে নিয়ে বাসায় পৌছে খেয়েদেয়ে সময়মতো অফিসে ফেরা সম্ভব নয়। নোটন-টােটন স্কুলের গেটে দাঁড়িয়ে ছিল। আলমকে দেখে এগিয়ে আসে। এ সময় তাদের বাড়ির দিকের কিছু খালি বাস পাওয়া যায়। বাসায় ফিরে আরেকবার গোসল সারে আলম। বাথরুম থেকে সে চেঁচায় ছিল—ফিরোজা খাবারের কতদূর? দু'এক ঘণ্টা লাগবে আরও—ফিরোজা উত্তর দেয়। আলম বের হয়ে দেখে টেবিলে খাবার তৈরি । নোটন-টোটন কালতলাতেই গোসল সেরে নিয়েছে। নোটন বলে-বাবা জানো, আজকে ক্লাস টেস্টে আমি ফাস্ট হইনি। আলম বলে---সামনের বার হােয়ো, হবে তো? নোটন মাথা নাড়ে ।

সিগারেট খায় না আলম । খাওয়ার পর এক খিলিপান এগিয়ে দেয় ফিরোজা । এখান থেকে বাস-স্ট্যান্ড সামান্য দূরে। সোজাসুজি রাস্তা হলে ফিরোজা তাকে বাস-স্ট্যান্ডে দেখতে পেত। কিন্তু রাস্তা বাঁক নিয়েছে। এই বাঁকে এসে একবার ফিরে তাকায় আলম। ফিরোজা এই দশবছর পরেও দরোজায় দাঁড়িয়ে । হঠাৎ করে হাত নাড়ার ইচ্ছে জাগে আলমের। চারপাশে তাকায় সে, কেউ দেখছে না দেখে সামান্য হাত তোলে। ফিরোজা বোধ হয় বুঝতে পারে না, কিংবা লজ্জা পায়, কিন্তু পাশে দাঁড়ানো নোটন-টােটন দু’হাত তুলে নাড়ে।

দিন দুই পর অফিস ছুটি হলে আলম ওয়ার্কশপে যায়। তার মোটরসাইকেল ঠিক হয়ে আছে। পরিচিত মিস্ত্রি বলে-আলম বাই, যন্ত্রটা বেঁচি দেন। আলম মাথা নাড়ে-হু, তুমি বললে আর আমি বেচে দিলাম, যে সার্ভিস দিচ্ছে। মিস্ত্রি বলে-নতুন একটা কিনি লন। আলম বলল-টাকা তুমি দেবে? মিস্ত্রি তখন হাসে।

বাড়ি ফিরে সে দেখতে পায় ফিরোজা শাড়ি-ব্লাউজের কাপড়ের ফেরিঅলাকে দরোজায় ডেকে শাড়ি উল্টে-পাল্টে দেখছে। পাশে দাড়ানো নোটন-টোটনের উৎসাহ আরও বেশি। এই দৃশ্যটাই হঠাৎ মন খারাপ করে দিল আলমের। এ-সময় শাড়ি-অলাকে কেন ডেকেছে ফিরোজা? এ-সময় এসব কেনাকাটা সম্ভব নয় ফিরোজা এই দশবছরে টের পায়নি? এসময় নিজের অক্ষমতাটুকুও টের পায় আলম, তার রাগ আরও লাফিয়ে উঠে। সে আর একবারও সেদিকে তাকিয়ে দেখে না। মােটর-সাইকেল রেখে উদাসভাবে ভেতরে ঢুকে যায়। ফিরোজা তার দিকে তাকিয়ে ঠোঁট টিপে হাসছে, সে বুঝতে পারে, কিন্তু সে প্রশ্রয় দেয় না। শোবার ঘরে বসে জামা-কাপড় পাল্টানোর পর খুব পুরনো একটা পত্রিকা দেখতে-দেখতে বাইরে সে সামান্যক্ষণ মৃদু কথাবার্তা শোনে । ফিরোজা কতক্ষণ পর ঘরে ঢোকে । আলম ভাবে টাকার কথা বলবে এখন । কিন্তু ফিরোজা পাশে বসে বলে-তুমি অত গম্ভীর কেন? আলম কথা বলে না। ফিরোজা আবার বলে—কী হল, কথা বলছ না কেন? আলম পত্রিকা থেকে চােখ তোলে না— শাড়িঅলা ডেকেছিলে যে বড়, পয়সা কোথায়? ফিরোজা হেসে ফেলে-বারে, আমি কিনলাম নাকি!

কেনার জন্যেই তো ডেকেছিলে । পছন্দ হল না। তাই কিনলে না | পছন্দ হলে কিনতে না? এ-সময় এতগুলো টাকা ।

ফিরোজা রাগে না-কে বলেছে তোমাকে আমি কিনতাম, পাগল, আমি শুধু দেখলাম ।

কিনবে না তো ডেকেছিলে কেন?

আহা, বললামই তো দেখতে, আমি শাড়িগুলো দেখলাম, দরদাম জিজ্ঞেস করলাম-ব্যাস আর কিছু নয়।

আলমের রাগ এরপর কমে যাওয়া উচিত ছিল, কিন্তু সে উল্টো চেচিয়ে উঠে-তুমি তো জানোই এ-সময় শাড়ি কেনা সম্ভব নয়, তবু ডাকবে কেন?

বারে, না-হয় নাই কিনলাম, তাই বলে দেখতেও পারব না?

না।

কেন?

এ-সময় সামান্য উষ্মা উঠে আসে ফিরোজার কথার সঙ্গে ।

অত কথা কেন, আমি বলছি তুমি কিনবে না-ব্যাস।

খুব শান্ত গলায় ফিরোজা বলে-শেষ শাড়িটা কবে কিনে দিয়েছে তা তো ভুলেই গেছি, শুধু দু’একটা শাড়ি দেখব তাও তুমি দেবে না?

এ-সময় তোমার শাড়ি কেনার শখ হওয়াও উচিত নয় ।

কেন-ফিরোজা এবার চেচিয়ে ওঠে-কোন শখ হবে না, ক’টা শাড়ি তুমি কিনে দিয়েছ আমাকে?

আমার কাটা জামা-কাপড় তুমি জানো?

আমি বলছি তোমার অনেক বেশি, কিন্তু আমার যা থাকা উচিত ছিল তার অর্ধেকও নেই।

ও-রকম খোটা দিও না। নেই তো নেই, এখন কী করতে হবে?

কী করবে। আবার, কিনে দেওয়ার মুরোদ নেই, আমার যা ইচ্ছে করব।

চুপ-আলম চেচায়-বেহায়া মেয়ে, আমি সারাদিন কী খাটছি পাগল হওয়ার দশা, অফিস থেকে ফিরতেই তুমি বকবক আরম্ভ করলে? -

আরম্ভ তাে করলে তুমি, আর শুধু তুমিই খাটছ, আমি কিছু করছি না? সারাদিন আমি পায়ের ওপর পা তুলে বসে থাকি?

সে-রকমই তো । তুমি কী জানো আমার কী খোজ রাখো, বাজার রেশন, নোটন-টােটনকে স্কুলে পৌছে দাও, বাসায় নিয়ে আসো; তার ওপর অফিসে একগাদা কাজ। তুমি কোনওদিন এসব নিয়ে আমাকে কিছু বলেছ?

বলিনি না, তুমি বলছ আমি বলিনি, বেশ তুমি আমার জন্যে কী করেছ, তুমি কবে আমাকে বেড়াতে নিয়ে গেছ, সারাদিন এত কিছুর পরেও এই অন্ধকার ঘরে পড়ে থাকি, কোনওদিন তো বলনি-চল বেড়িয়ে আসি, তুমি কোন খোজটা রাখো আমার মনের?

আলম সে-সব কথা উড়িয়ে দেয়-আরে রাখো, আমন আলগা ফ্যাচফ্যাচ করো না।

ফিরোজা আর কথা বাড়ায় না। ঘর ছেড়ে বেরিয়ে যাওয়ার আগে চৌকাঠে একবার থামে, আঁচলে চােখ মােছে। সন্ধ্যার আগে নােটন-টােটন সামনের ছােট মাঠ থেকে ফিরে হাত-মুখ ধুয়ে পড়তে বসে। আলম সে-ঘরেই বসে থাকে, সেই পুরনো পত্রিকাই উল্টেপাল্টে পনেরবার দেখে। সন্ধ্যার পর ফিরোজার আওয়াজ পাওয়া যায় রান্নাঘরে। তবে বোধ হয় রাগ করেনি- আলমের মনে হয়। অর্থহীন এক ঝগড়া বাঁধিয়ে ফেলেছে সে; এখন বেশ বুঝতে পারছে। তবে ফিরোজা এখন রান্নাঘরে, তবে ফিরোজা রাগ করেনি—এ-রকম মনে হতেই আলম বেশ উৎফুল্ল বোধ করে। নিজের দোষ আর লজ্জাটুকু ভোলার জন্যে সে আরও কতক্ষণ অপেক্ষা করে। পত্রিকাটা হাতে নিয়েই সে আস্তে-আস্তে রান্নাঘরের দরোজায় এসে দাড়ায়। ফিরোজা মুখ খুব নিচু করে চাল বাছছে। আলম আস্তে ডাকে-ফিরোজা। একটু চমকে উঠেছিল ফিরোজা, ডাকটা আলমের বুঝতে পেরেই শক্ত হয়ে যায়। আলম আরও একটু এগিয়ে যায়, পাশে বসবে কি বসবে না ভাবে, দাঁড়িয়ে থেকেই বলে।--তুমি রাগ করো না ফিরোজা, অফিস থেকেই হঠাৎ মন খারাপ, কথা বলবে না ফিরোজা ? ফিরোজা মাথা গুজে থাকে, কোনও সাড়া-শব্দ করে না, চাল বাছা হাতও আগের মতো দ্রুত চলছে না। আলম আবার ডাকে । ফিরোজা ঝট করে মুখ ফেরায়, কিন্তু কথা বলতে সময় নেয়—তুমি কথা বলো না আমার সঙ্গে, যাও । খুব কেঁদেছে ফিরোজা, দু'চোখ খুব লাল, এখনও জলের পরল পড়ে আছে। ফিরোজার কথা শুনে একটুও রাগে না আলম, ভেজা লাল দু'চোখ দেখে সে দমে যায়। নিজের অন্যায় বোধটুকু আবার তার জেগে ওঠে । এখন হবে না বুঝতে পেরে সে রান্নাঘর থেকে সরে আসে।

ফিরে এসেও তার ভালো লাগে না। কতক্ষণ নোটন-টোটনের বই-খাতা উল্টেপাল্টে দেখে । শেষে ঘর ছেড়ে রাস্তায় নেমে ঘুরে বেড়ায় । বাসস্ট্যান্ডের উল্টোদিকে একটা মাঠ আছে। সেখানে গিয়ে বসে থাকে। মাঠে অনেক লোকজন বাতাস গায়ে মেখে গল্প করছে। আশেপাশে কখনও বাদাম অলা, এই রাতেও কখনও আইসক্রিম, কখনও দু’একজন সন্দেহজনক লোক । সে মাঠের এককোণে হু-হু বাতাসের মধ্যে বসে থাকে। চারপাশের হইচই সে লক্ষ্যই করে না। মাথা গুজে বসে থাকতে-থাকতে হঠাৎ তার কান্না পায়। সে খুব চেষ্টা করে রুখে রাখার। এই বয়সে কান্না, তার লজ্জা লাগে । স্বামী-স্ত্রীর এ-রকম ছোটখাটাে ঝগড়া হবেই, তার জন্যে কাঁদবে কেন সে? কিন্তু ক্রমশ সে বুঝতে পারে শুধু আজকের বিকেলের ঘটনার জন্যে তার কান্না পাচ্ছে না, আসলে অনেকদিন ধরে তার কাঁদতে ইচ্ছে করছে, অনেকদিন ধরে কান্না তৈরি হয়েছে তার ভেতর । সব এখন বেরিয়ে যাবে বলে উঠে আসছে গলা ছাড়িয়ে । বাতাসের মধ্যে সে কেঁপে ওঠে ।

বহুক্ষণ পর চোখ তুলে সে দেখল মাঠ অনেক ফাঁকা। লোকজন, বাদাম অলা প্ৰায় সবাই চলে গেছে। নিজেকে খুব হালকা মনে হল তার। কত দুঃখ তার একসঙ্গে কুণ্ডলী পাকিয়ে উঠে চলে গেছে। তখন শুধু ফিরোজার প্রতি সামান্য অভিমান । রাত হয়েছে সে বুঝতে পারে। ফিরোজা আর নোটন-টােটন বাড়িতে একা, সে উঠে বাড়ির দিকে পা বাড়ায় । বাসস্ট্যান্ডের আগের বাকিটা ঘুরলেই সে বাড়ির দরোজা দেখতে পায়, একপাশে এক মূর্তি দাঁড়িয়ে আলো-ছায়ায়। আলম ক্রমশ আরও এগোলে সেই মূর্তি দরোজা থেকে সরে যায়। ঘরে ঢুকতেই পাশের ঘরের জানালায় মুখ এনে নোটন বলে-আমরা সবাই খেয়েছি, মা বলেছে তােমাকে খেয়ে নিতে। আলম দ্বিরুক্তি করে না। ফিরোজার দৃষ্টি আকর্ষণের কোনও চেষ্টা না-করে সে খেয়ে নেয়। নিজেই বাসন-কোসন গুছিয়ে রাখে । শেষে পেছনের বারান্দার এককোণে চেয়ার টেনে বসে পড়ে। অনেক দিন পর রাতের আকাশের দিকে চোখ পড়ে তার। আকাশে অনেক তারা, পশ্চিম দিকে একটু হেলে পড়া সম্পূর্ণ চাঁদ। সামনে যে বড় গাছ, বাতাসে তার পাতার আওয়াজ পাওয়া যাচ্ছে। ভেতরের দু’ঘরের আলো নিভে গেছে। ফিরোজা কি শুয়ে পড়েছে, ভেবে তার আরও অভিমান হয়। তার ঘুম পাচ্ছে, কিন্তু ফিরোজার পাশে গিয়ে সে এখন কীভাবে শোবে ভেবে তার লজ্জাও করছে। এ-সময় ফিরোজা বারান্দায় আসে। পেছনে দরোজায় মৃদু আওয়াজ হতেই সে চোখ ফিরিয়ে দেখে ; ফিরোজা তার পিছনে এসে দাঁড়ায় । আলম চুপ করে কালো-কঠিন গাছের দিকে তাকিয়ে থাকে। ফিরোজা বলে—শোনো, তুমি আমার সঙ্গে বিকেলে ঝগড়া করলে কেন?

আশেপাশে কারও জেগে থাকার কোনও সাড়াশব্দ নেই। আলম নাগালের মধ্যে দাঁড়ানো ফিরোজাকে ঝটিতি টেনে এনে উদভ্ৰান্তের মতো চুমু খায়। চুম্বনের পূর্বমুহূর্ত পর্যন্ত শক্ত ছিল ফিরোজা, পরমুহূর্তে সে উদভ্ৰান্ত না-হলেও সহজ হয়ে ওঠে। পরে সে আলমের মাথায় হাত রেখে উঠে দাঁড়ায়, বলে-আমার খুব খারাপ লেগেছিল, তুমি তো কখনও আমাকে ওভাবে বলো না । আলম বোকার মতো মাথা নাড়ে-হঠাৎ করে ফিরোজা, হঠাৎ করে এমনিতেই মনটা খারাপ হয়ে গেল, তোমাকে শাড়ি দেখতে দেখে আমার মনে হল বহু আগেই তোমাকে একটা নতুন শাড়ি দেয়া উচিত ছিল আমার, কিন্তু অতটুকু পয়সাও অনেকদিন হাতে জমছে না খেয়াল হতেই তোমার ওপর রেগে গেলাম। আসলে আমি তোমার ওপর একটুও রাগ করিনি। একটু থেমে সে বলে—তুমি খুব কষ্ট পেয়েছ না? ফিরোজা কথা বলে না, সে আলমের চুল মুঠো করে চেপে ধরে আবার ছেড়ে দেয়। আলম বলে---সামনের মাসে তোমাকে একটা সুন্দর শাড়ি কিনে দেব, আমি কিনে দেব পছন্দ করে। ফিরোজা মাথা নাড়ে--উহু, আমার তো টাকা নেই, তুমি আমাকে টাকা দিও, আমি তোমাকে শার্টের কাপড় কিনে দেব পছন্দ করে। না, সামনের মাসে শাড়ি কেনা হবে, আলম আবার ফিরোজাকে কাছে টেনে আনে, আর শোনো কাল আমরা বেড়াতে বের হব। ফিরোজা বাচ্চার মতো মাথা দোলায়-- কোথায়? তুমি যেখানে যেতে চাইবে আলম বলে-পার্কে সিনেমায় কিংবা কোনও ভালো হােটেলে খাব।

সত্যি-ফিরোজা জিজ্ঞেস করে। ঘাড় কাত করে আলম-সত্যি, কাল তো হাফ-ডে, আমি সবকিছু ঠিক করে নিয়েছি, নোটন-টােটনকে পাশের বাসায় রেখে বিকেলে আমি আর তুমি যাব। ফিরোজা কতক্ষণ চুপ করে থেকে আস্তে বলে-আমি অনেকদিন বাইরে যাই না, জানি তোমার তো সময় হয় না, তাই তোমাকেও বলি না, কিন্তু মাঝে-মাঝে খুব খারাপ লাগে, সারাদিন শুধু ঘরের মধ্যে, শেষ কবে বেড়াতে গিয়েছি সে তো ভুলেই গেছি. কাল আমরা সত্যি যাচ্ছি। তো? আলম হাসে-সত্যি, তুমি ঠিক করো কোথায় আমরা যাব। ফিরোজা মাথা হেলিয়ে সামান্যক্ষণ ভাবে-ঠিক আছে, আমি ভেবে-চিন্তে তোমাকে বলব। সামান্যক্ষণ চুপচাপ গেল। ফিরোজা হাত ধরে টানে আলমের-চলো। আলম উঠে না-এখানেই থাকি বসে, কী সুন্দর রাত। কিন্তু সে পেছনে ফিরে ফিরোজার চোখের দিকে তাকিয়ে হেসে ফেলে বলে-ও বুঝেছি, চলো চলো।

সকালে রোজাকার মতো ঘুম ভাঙে আলমের। জানালা গলিয়ে রোদ এসেছে মশারির ওপর, ময়লা মশারির একাংশ হলুদাভ উজ্জ্বল। ঘরের ভেতর যে-দু’টাে চড়ুই বাসা বেঁধেছে তারা উড়ে যায়। বিছানার চাদরের এদিক-ওদিক দু-তিনটে ছোট-বড় ফুটাে । আলম সে সব গুণতে গুণতে উঠে পড়ে। কলঘরে ব্রাশ হাতে বসার আগেই সে রান্নাঘরের দরোজার কাছে ফিরোজাকে দেখে । তার পায়ের শব্দে ফিরে তাকিয়ে ফিরোজা হাসে। গতকালের কথা মনে পড়লে আলমও হাসে। অনেকদিন পরে তারা দু'জন-দু’জনকে নতুন করে দেখছে। গতরাতের স্মৃতি বিয়ের ঠিক পরের দিনগুলোর মতো সজীব । অনেক দিন পর ঝগড়াটা হয়েছিল ভাগ্যিস ।

আলম দাঁত মেজে উঠে আবার ব্যস্ত হয়ে যায়। আজ অবশ্য রেশন আনার ঝামেলা নেই। কিন্তু নাস্তা খেয়ে বাজার থেকে ফিরে আসতেই সময় পেরিয়ে যায়। গোসল সারার আগে সে পুরোনো কাপড় আর তেল দিয়ে ঘষে-ঘষে মোটরসাইকেল সাফ-সুতরো করে। পানি দিয়ে চাকা, মাডি-গার্ড এসব ধুয়ে-মুছে নেয়। ইদানীং খুব ফলস্ স্টার্ট নিচ্ছে আর স্পিড বেশি তুললেই স্পার্কিং আরম্ভ হয়ে যাচ্ছে-ওয়ার্কশপের লোকজনও এসব সারাতে পারছে না । গোসল'-টোসল সেরে নোটন-টোটনকে মোটরসাইকেলের পেছনে বসিয়ে স্কুলে নামিয়ে দেয়। আজ হাফ-ডে ।

দুপুরে লাঞ্চের সময় সে নোটন-টােটনকে নিয়ে ফিরে আসে। দুপুরে খাওয়ার পর বাসন-কোসন গুছিয়ে রেখে ফিরোজা আলমের পাশে এসে শোয় । বলে- কোথায় যাব ঠিক করেছি জানো? আলম মাথা নাড়ে-উহু, কোথায়? কোথাও না—ফিরোজা খুব দ্রুত বলে। আলম একটু বোকার মতো তাকালে ফিরোজা বলে কোথাও না মানে আমরা পার্কে যাব না; সিনেমায় যাব না; কিন্তু কী করব জানো, তোমার মোটরসাইকেলের পেছনে চেপে বসে আমি শুধু ঘুরব, শুধু রাস্তায়-রাস্তায় ঘুরব, দেখি তুমি কত দূর আমাকে নিয়ে যেতে পার। আলম খুব সাহসী গলায় বলে-ঠিক হ্যায়, আমি তোমাকে এমন-এমন জায়গায় নিয়ে যাব তুমি খুব অবাক হবে। তা তো হবই-ফিরোজা মাথা দোলায় কতদিন ঘর থেকে বের হই না জানো, এতদিনে কত বদলে গেছে শহর । আলম সামান্য মৃদু গলায় বলে—তা বটে, আমি সব জানি, কিন্তু সময় কোথায় বলো— বাজার, রেশন, নোটন-টোটনদের স্কুল, অফিস করে সারাটা সময় চলে যায়, আসলে আমিও অনকদিন পর বের হব ।

দুপুরাটা গল্প করে কাটে। ফিরোজা আলমের চুল থেকে হাত সরায় না। বিকেলের আগে-আগে উঠে তারা জামা-কাপড় বদলে নেয়। পুরনো ঐট্রাঙ্ক থেকে বের করে ফিরোজা একটা পুরনো শাড়ি পরলে আলম অবাক চোখে তাকিয়ে থাকে- তুমি আসলেই মাৰ্ভেলাস... নোটন দেখ তো, তোমার মাকে কেমন লাগছে? ফিরোজা নোটন-টােটনকে ডেকে বলে— বাবুরা আমরা একটু বাইরে যাচ্ছি, তোমরা দু’জন রঞ্জুদের বাসায় থেকো, ফেরার সময় তোমাদের জন্যে চকলেট নিয়ে আসব।

নোটন-টোটন মাথা নাড়ে। দরোজায় তালা দিয়ে চাবি পকেটে রাখে আলম । নোটন-টােটন রঞ্জুদের বারান্দা থেকে হাত নাড়ে। আলম বলে-ইশ, কতদিন পর আমরা বের হচ্ছি। তোমার কথাই ঠিক ফিরোজা, কোনও নির্দিষ্ট দিকে নয়, যেদিকে চোখ যায়, শুধু সেদিকেই যাব।

বাকিটুকু পেরোতেই সামান্য স্পিড বাড়ায় আলম, ফিরোজাকে বলে-যেদিকে যায় মোটরসাইকেল সেদিকেই আমরা । সামান্য এগিয়েই সে দেখতে পায় রেশন শপ; ফিরোজাকে দেখায়-ওই যে ওখান থেকে রেশন তুলি ... আর ওই যে বাজার, আর কতকটা এগিয়ে সে বাজারের দিকে আঙুল উচিয়ে দেয় এখন তো ভিড় নেই, সকালবেলা দেখলে বুঝতে কী অবস্থা। খুব আমুদে গলায় কথা বলতে-বলতে আলম স্পিড তুলে এগিয়ে যায়। বেশ দূরে নোটনদের স্কুল দেখে সে স্পিড ক্রমশ কমিয়ে আনে। স্কুলের সামনে এসে থেমে যায় হঠাৎ—এটা কি জানো, উহু সাইনবোর্ড দেখলে হবে না, এটা হচ্ছে নোটন-টোটনদের স্কুল। ফিরোজার দেখা শেষ হওয়ার আগেই আলম ইঞ্জিন স্টার্ট দেয় । খুব একটা ভাবছে না আলম, মোটরসাইকেল যেন অনেকটা নিজের ইচ্ছেয় এগিয়ে যাচ্ছে। অফিসের সামনে এসে সে খুব কায়দা করে মোটর-সাইকেল থামায়-এবার বলো আমরা কোথায় এসেছি? ফিরোজা কিশোরীর মতো মাথা দোলায়--কীভাবে বলব বলো, একটু সন্দেহ হচ্ছে বই-কী । ঠিক সন্দেহ-আলম জোরগলায় বলে- ওই যে পশ্চিম দিকে কাচের জানালায় নীল রঙ, ওই ঘরে আমরা বসি। এরপর তারা আরও এগিয়ে যায়। দু’পাশের লোকজন, গাড়িঘোড়া, ভাঙাচোরা রাস্তা। এসবের মধ্যেও আলম খুব স্বচ্ছন্দে মোটরসাইকেল এগিয়ে নেয়। আর এবার দেখ, সে বলে, ওখানে আমি মোটরসাইকেল সারাই, ওই যে, নিবেদিতা ওয়ার্কশপ, চেনাজানা লোক আছে, আলাপ করবে? ফিরোজা বলে-ধ্যাৎ । মোটরসাইকেল আরও এগিয়ে যায় । তোমাকে একটা মজার জিনিস দেখাব--- আলম বলে-ওই যে ডানপাশের একতলা হলুদ বাড়িটা, কে থাকে জানো, ব্যাটা সুদখোর হান্নান, আমাদের সঙ্গেই কাজ করে, আমি দরকার পড়লেই ওর কাছ থেকে টাকা ধার নেই, সুদ নেয় নিক তবু ভালো, আজকাল কে ধার দেয়?

আলমের কাধের ওপর একটা হাত রেখেছে ফিরোজা, আর এক হাতে সিটের একাংশ ধরে ব্যালান্স ঠিক রাখছে। এসব জায়গার কথা প্রায় সে আলমের মুখে শুনেছে। আজই সে প্রথম দেখছে। এবার নিশ্চয় আরও এগিয়ে যাবে তারা, সে ভাবে । আলম দ্রুত স্পিডে দু’পাশ থেকে ক্রমশ এগিয়ে যাচ্ছে। স্পার্কিং আরম্ভ হলে সে স্পিড সামান্য কমিয়ে আনে। আরও কিছুটা এগিয়েই রাস্তাঘাট চেনা-চেনা মনে হয় ফিরোজার। আর একটু এগিয়েই ফিরোজা দেখতে পায় তাদের বাড়ি, রঞ্জদের বারান্দায় নোটনকেও সে হয়তো এক পলক দেখে । তারপরে ক্রমশ তার চোখে পড়ে রেশন শপ, নোংরা ময়লা কাদায় একাকার বাজার । সে আলমকে বলে- তুমি আবার এ-পথে এলে যে বড়, এ-পথে আমরা তো প্রথমেই ঘুরে গেছি। কই-- আলম বলে, তারপরেই সে-ও অবাক হয়— আরে তাই তো, একদম খেয়াল ছিল না। ততক্ষণ তারা নোটন-টােটনদের স্কুল ছাড়িয়ে এসেছে। ফিরোজা ভাবে এবার তারা অন্যদিকে ঘুরবে। আলমকেও খুব নিরুদ্বেগ দেখায়। কিন্তু একটু পরেই ফিরোজার চোখে পড়ে আলমের অফিস, তারপর নিবেদিতা ওয়ার্কশপ, আরও এগিয়ে সুদখোর হান্নানের বাড়ি। ফিরোজা রেগে যায়—কী ইয়ার্কি মারছ, তুমি কি একই রাস্তায় ঘুরাবে আমাকে? দাড়াও ঘুরাচ্ছি, কী যে হল, বেখেয়ালে এক রাস্তায়ই চলে এলাম— আলম মোটর-সাইকেলের ওপর খুব নজর রাখতে রাখতে বলে ।

কিন্তু সামান্য পরেই ফিরোজা প্রায় চেচিয়ে ওঠে। আবার মোটর সাইকেল তাদের বাড়ির সামনে ফিরে এসেছে। তারপর ক্রমশ রেশনশপ পেরিয়ে বাজারের দিকে এগিয়ে যাচ্ছে। ফিরোজা গম্ভীর গলায় বলে- আমাকে নামিয়ে দাও, এসব ঢঙের দরকার নেই, তুমি কি অন্য রাস্তা চেনো না? কিন্তু আলমের কাধে রাখা ফিরোজার হাত টের পায় আলম কাপছে। সে বলে- না না, দাড়াও ফিরোজা, আমি দেখছি। সে মোটর সাইকেলের ওপর ঝুকে পড়ে; তীক্ষু চোখ রাস্তার দিকে তাকায়, বারবার অর্থহীন গিয়ার বদলায় সাইকেলের, স্পিড বাড়িয়ে আবার কমিয়ে আনে। কিন্তু মটরসাইকেল ক্রমশ তাদের নিয়ে বাজার পেরিয়ে আসে, রেশনশপ ছাড়িয়ে আরও এগিয়ে তারা দেখতে পায় নোটন-টােটনদের স্কুল, আলমের অফিস, নিবেদিতা ওয়ার্কশপ । আলম খুব চেষ্টা করে, সাইকেলের কত কী ঘোরায়-নাড়ায়, ফিরোজা তার কিছু বোঝে না, খুব কাঁপছে আলম সে শুধু বুঝতে পারে। আবার তারা ফিরে আসছে ফিরোজা টের পায়। আলমের হাত কেঁপে যায় মোটরসাইকেলে, সে চেচিয়ে উঠে- ফিরোজা আমি চেষ্টা করছি ফিরোজা, কিন্তু বাজার, রেশনশপ, নোটনদের স্কুল, ওয়ার্কশপ, সুদখোর হান্নানের বাড়ি- আমি বের হতে পারছি না, ফিরোজা আমি বের হতে পারছি না।

The Circle

Moinul Ahsan Saber

Translated by Masrufa Ayesha Nusrat

Feroza had slipped out of bed at dawn, carefully lifting one corner of the mosquito net as she did so. Alam recalled her nudging him before she left. It was a pair of sparrows who eventually got him out of bed. Sunlight was streaming into the room through the window, brightening that part of the grimy mosquito net it had fallen upon. Alam shifted his gaze from the sparrows towards the patch of light, staring at it for some time. Both his sons were studying on the veranda. Sitting up in bed, he could see the eldest boy’s head rocking back and forth. Alam stretched, taking his time. These were his only moments of pleasure during the entire day. He wanted to spend this brief interlude as he pleased. There wouldn’t be a minute to spare once he was out of bed. He looked at himself in the small, dull mirror on the wall, turning away before that inevitable pang of disappointment took hold. But a single glance had revealed everything – the dark circles beneath his eyes, sunken cheeks, a torn and grubby undershirt. He smiled to himself as he stood in front of the mirror, looking down at the toothbrush he was putting toothpaste on.

Feroza threw him a glance as she squatted at the tap next to the kitchen. Alam loved her immensely, but ten years of marriage had only exhausted them. He hadn’t been able to give her many of the things a loving husband should. The area around the tap was slippery with mud even in summer. Dark mould had gathered in places. Weeds had grown in the gaps in the cement and the cracks in the peeling plaster. There was a large tree close by; its tough, blackened trunk visible from where she was squatting. Alam rinsed his mouth as he took this all in. By this point, Feroza had made breakfast – wheat rotis with stir-fried vegetables, or some jaggery* and leftovers from the night before, if there were any. A small, old table stood on the veranda, which caught the morning sun at the back of the house. The four of them just about fitted around it. Many things had fallen apart in their household over ten years of poverty, but in all this time Alam hadn’t broken this one rule – Feroza always sat by his side at this hour. A bond grew between them during this short meal, even if momentarily. Feroza could do the impossible. Knowing that they would soon be weighed down by work, she kept everyone amused now. Serving Noton and Toton, she asked Alam, ‘You remember everything you have to do before leaving for work?’ Alam shook his head gravely, ‘I don’t!’ ‘Then listen.’ She counted the tasks off on her fingers: ‘One, go to the bazaar; two, pick up the rations; three, drop Noton and Toton off at school.’ Alam nodded, ‘As you wish, your highness. It shall be done.’ The rations had to be picked up once a week, while the other two were daily chores. But this was how each day began.

The strains of this little pleasure had died by the time he stepped out with the shopping bag. He was reminded of how little he could afford to spend. The bazaar was a stone’s throw away, which was fortunate; otherwise, he would have had to rush to work straight afterwards. A great deal of time was wasted trying to find the lowest prices. He had the desire, but not the means, which infuriated him. He had no choice but to bring home stale, half-rotten food bought cheap. There was no time to catch his breath – putting the shopping bag down, he rushed out again with the ration card and another bag. At the ration store, there would be a long queue of people who also had to go to work. As they waited, they crunched on and spat out inflation, politics, and social degeneration like people eating peanuts. It took a long while for his turn to come. Back home, he bathed quickly; he had 45 minutes to get to work. Long years of habit had accustomed Alam to this routine – he kept pace with the clock and was never late at work. As he hung out his clothes to dry on the veranda after his bath, he could see his children waiting at the table in their school uniform. Alam was used to eating quickly too. Feroza chided him every day, ‘Never mind if you’re a little late, why do you have to eat so fast?’

Serving him some rice, Feroza said, ‘You’re working too hard, look how thin you’ve become.’ At these moments, the realisation that there was so much love beneath the poverty and exhaustion leaped out at Alam. This was the reason Alam loved Feroza so much. Maybe Feroza had spoken without much thought, and what else could she have said anyway? Nevertheless Alam could feel her sincerity. Feroza did not eat with him at this time. She still had too much to do. Her face reddened by the flames on the stove, she would feed Alam, Noton and Toton, see them off, clean the house, finish the cooking, wash the clothes… this was how her day would be spent. Noton and Toton returned home in the afternoon and Alam, just before darkness fell.

Alam had an old motorbike. He had bought it with a loan soon after his marriage. It was still very useful. He had sent it to the workshop for repair the day before yesterday; it often gave him trouble these days. Even if it needed repairs two or three times a month, he was able to do it cheaply because he knew the people at the workshop. He would go to the office after dropping Noton and Toton off at their school. From the street they waved at Feroza as she stood at the door.

Alam hailed a rickshaw. He didn’t usually care for one, but as the motorbike wasn’t an option, and waiting for the bus during rush hour was pointless – Alam decided to get it over with.

Getting off the rickshaw, and paying the fare, Alam paused for a moment.

When the children had disappeared through the school gate, he climbed on to the pavement. With fifteen minutes to spare, he could walk to his office and be in good time.

Not that it mattered even if he were five or ten minutes late. There was no fear of having to provide an explanation. Many of his colleagues were frequently late. Leaving early wasn’t a problem either. But Alam couldn’t do it. Arriving on time had become a strict habit. It wasn’t as though he was bothered by the ethics of it. Nor did he ever consider ringing in sick. He just couldn’t shrug off the habit of punctuality.

Those who were in the office already were busy chatting. Young Asif had joined recently, having worked the back channels to get a job. Weighed down by nothing besides his own responsibilities, he was holding forth as confidently as always. Sitting in his chair and wiping his face with a handkerchief, Alam turned his attention to what Asif was saying. It was about a film he had watched yesterday. Alam knew the story would soon be swept away. This was a daily routine. The discussion would then cycle through price-rises, world politics, the state of the roads or hospitals or transportation, crowded buses, inflation, the insolence of rickshaw-drivers…

As soon as Alam leaned back in his chair, he felt the exhaustion his body had gathered through the morning. There wasn’t a thing he could avoid – the bazaar, the ration shop, taking his children to school and bringing them back home – all of these were his responsibilities. But when the fatigue crashed over him during these brief moments of respite, he realised how swiftly he was destroying himself. He could not let go of this idea, even as he pulled his half-finished file from yesterday towards himself. How quickly time was flying. How quickly his youth had been spent. If it hadn’t been for the bond of Feroza’s love, he would have walked far away from everything by now. This monotonous life – sometimes he had an urge to scream! But he lacked the courage or strength. Their time together, Feroza’s and his, was over. It felt this way after just ten years, and the regret bubbled up through the thought: We’re finished in just ten years. The layers of deprivation and tiredness had thickened around him, adhering even closer. He longed to do something unexpected, break a rule in some way. But not even a simple family picnic or the indulgence of dinner at a fancy restaurant seemed within reach anymore. He realised that he was no longer capable of doing these things. If only he had the courage to do something out of the ordinary.

There was no time to spare even at lunch. The children would wait for him at the school gate. This was when Alam unhesitatingly stole ten or fifteen extra minutes after his lunch hour. Taking Noton and Toton home, eating his lunch, and coming back on time was impossible. They were waiting at the school gate, coming towards Alam when they spotted him. At this hour they could take an empty bus home. Alam bathed again, shouting from the bathroom, ‘How long will lunch take, Feroza?’ ‘A couple of hours!’ she smiled. When he came out the food was on the table. The boys had bathed beneath the tap in the yard. Noton said, ‘Do you know, Baba, I didn’t come first in the class test today.’

‘Next time, all right?’ Alam said. Noton nodded.

Alam did not smoke. Feroza handed him a paan after his meal. The bus-stop was a short walk from the house. If the road had been straight Feroza could have followed him with her eyes all the way, but there was a bend. When he reached the bend, Alam looked back. Even after ten years, Feroza still stood there. And today, Alam had a sudden urge to wave. Looking around furtively to see if anyone was watching, he half-raised his arm. Perhaps Feroza didn’t see, or she was embarrassed, but the children standing next to her waved both hands.

A couple of days later, Alam went to the workshop on his way back from the office. His motorbike had been repaired. The mechanic he knew said, ‘Alam Bhai, sell it off.’ Alam shook his head. ‘Just because you say so. Do you know the service it gives me?’ The mechanic said, ‘Buy a new one.’ Alam asked, ‘Are you paying?’ The mechanic smiled.

When he got home he found Feroza examining saris brought by a peddler. The children standing by her seemed even more excited. The sight depressed Alam. Why had Feroza called the peddler now? Hadn’t she realised, even after ten years, that buying anything at this time was out of the question? Alam realised his own inadequacy even more, which heightened his anger. Without sparing another glance, he parked his motorbike and entered the house with a show of disinterest. He knew Feroza was looking at him and smiling mischievously, but he didn’t indulge her. Having changed out of his work clothes, he sat in the bedroom reading an old magazine and listening to the faint conversation outside. Feroza came into the room after some time. Alam assumed she’d ask for money, but she only sat next to him and said, ‘Why so serious?’ Alam was silent. Feroza continued, ‘What’s wrong? Why aren’t you talking?’ Without raising his eyes from the magazine, Alam said, ‘What are you looking at all those saris for, where’s the money?’ Feroza laughed: ‘Who said I was buying?’

‘What else did you call him in for? You aren’t buying any because you didn’t like any of them. Else you would have. Imagine spending so much money at this time of the month!’

Feroza refused to be angry. ‘Who told you I was going to buy anything, am I mad? I was just looking.’

‘Then what did you call him in for?’

‘I just told you, to have a look. That was all I did, besides asking for the price, nothing else.’

Alam’s anger should have subsided by now, but he shouted back instead, ‘You know very well that we can’t afford a new sari now, why did you have to call him in?

‘What if we can’t afford it, can’t I even have a look?’

‘No!’

‘Why not?’

There was a little indignation in Feroza’s voice.

‘What’s all this shouting about? I’m saying you can’t buy a sari, and that’s final.’

Feroza said very calmly, ‘I don’t even remember when you last bought me a sari. You won’t even allow me to look at them?’

‘You shouldn’t even be fancying a new sari now.’

‘Why not?’ Feroza burst out. ‘Why can’t I? How many saris have you ever bought me?

‘Have you any idea how many clothes I have?’

‘I’m not saying you have a lot, but I don’t have even half as many as I should.’

‘Don’t you taunt me. So you don’t have them. What must I do now?’

‘What can you do? You don’t have what it takes. I’ll do as I please.’

‘Shut up!’ yelled Alam. ‘You brazen woman! Here I am driving myself crazy, working day and night, and you start nagging the moment I come home.’

‘It was you who started, and do you think you’re the only one working day and night? Do I lie around on the sofa all day?’

‘Of course. Have you any idea of the things I do? Have you ever tried to find out? Shopping, rations, taking Noton and Toton to school, bringing them back home, and on top of all this a mountain of work at the office. Have you ever talked about any of this with me?’

‘I haven’t, you say I haven’t. Very well, what have you ever done for me? When was the last time you took me out? I’m cooped up at home in the darkness every single day! I don’t remember you ever saying: “Let’s go out!” Do you even know what’s in my heart?’

Alam brushed her aside. ‘Just stop it. Cut out all this whining!’ Feroza didn’t prolong the argument. Before leaving the room, she paused at the threshold, dabbing at her eyes with the end of her sari. Before darkness fell Noton and Toton returned from the small field opposite their house, washed themselves and sat down to study. Alam kept sitting in the bedroom, flipping over the pages of an old magazine at least 15 times. In the evening, Feroza could be heard moving about in the kitchen. Then she isn’t angry, concluded Alam, feeling quite cheerful as soon as the thought occurred to him. He waited a little longer to overcome his guilt and embarrassment before strolling to the kitchen door with the magazine to stand there. Feroza was sorting through the rice, her head bowed low over the pot. Alam called her softly, ‘Feroza.’ Startled, she stiffened when she realised who it was. Alam went nearer, wondering if he should sit down by her side, but remained standing while he spoke. ‘Please don’t be angry, Feroza, I’ve been upset since I went to the office. Won’t you talk to me?’ Feroza didn’t look up, saying nothing; the movements of her hands slowed down. Alam called her again. Feroza jerked her head to look at him, but took her time before replying. ‘Don’t talk to me. Go away!’ She had wept uncontrollably, her eyes still red, the tears still glistening in them. Alam felt no anger, but her wet eyes made him lose courage. His guilt resurfaced. He left, realising it wouldn’t work right now.

He wasn’t at peace back in the bedroom either. For some time he turned over the pages of the children’s books. Eventually he went out of the house to wander the streets. There was a field opposite the bus stop, where he sat for a while. A number of people were enjoying the fresh air and chatting. People selling peanuts or ice-cream passed every now and then, a couple of suspicious characters too. He sat in a corner of the field, feeling the wind in his face, and paying no attention to the commotion around him. With his head buried in his knees, he suddenly felt like crying. He tried very hard to stop himself, embarrassed by the possibility of weeping at his age. Husbands and wives had minor quarrels like these all the time – why should they make him cry? But gradually he realised that his need to cry wasn’t because of today’s incident alone; he had been wanting to weep for quite some time; the tears had been building up within him. He shivered in the wind.

He looked up after a long time to find the field had almost emptied out. The people, the vendors, all of them had disappeared. He felt much lighter now. All his sadness had spiralled up into the sky. The only thing he felt hurt about was Feroza’s behaviour. It was late, he realised. Feroza, Noton and Toton were home alone. He set off homewards. As soon as he rounded the corner past the bus stop, he could see his front door, a figure standing by it in the darkness. It moved away as he drew closer. The moment he entered, Noton peeped through the window of the next room. ‘We’ve eaten. Ma said you should, too.’ Alam did not protest, eating without trying to attract Feroza’s attention, and putting away the plates afterwards. Finally he drew a chair to the corner of the veranda at the back of the house and sat down in it. After a long time, his eyes settled on the night sky. Tonight it was studded with stars, with the moon declining a little to the west. He could hear the leaves rustling in the large tree in front of the house. The lights in the two rooms had been switched off. Had Feroza fallen asleep? The thought deepened his hurt. He was sleepy too, but even the idea of lying down next to Feroza was humiliating. At that instant Feroza came out onto the veranda. A muted sound at the door made Alam look behind him. Feroza came up behind him. Alam stared at the unforgiving, darkened tree. Feroza said, ‘Listen, why did you fight with me?’

There was no sign of anyone nearby being awake. Feroza was within reach, Alam pulled her to himself and kissed her frantically. She had appeared unrelenting till he kissed her, but the very next moment she loosened up, even if she wasn’t overwhelmed. Afterwards, she rose to her feet, touching his head, and said, ‘I felt awful, you never speak to me that way.’ Alam nodded foolishly. ‘It was very sudden Feroza, I felt miserable, when I saw you examining the saris. I felt I should have bought you a new one long ago, but it’s been a long time since I’ve been able to save enough to afford it, and as soon as I realised this I lost my temper with you. Actually I wasn’t angry with you at all.’ Pausing, he added, ‘You were really hurt, weren’t you?’ Feroza did not answer, grabbing a fistful of Alam’s hair and then releasing it. Alam told her, ‘I’ll buy you a beautiful sari next month, I’m going to choose it myself.’ Feroza shook her head, ‘No. I have no money, you must give me some, I’m going to pick out a shirt for you.’ Alam drew her close again. ‘No, we’re getting a sari next month. And listen, we’re going out tomorrow.’ Feroza nodded like a child. ‘Where will we go?’ ’Wherever you want to,’ answered Alam. ‘To the park, or for a movie, or a good dinner somewhere.’

‘Really?’ asked Feroza. Alam nodded. ‘Really. We have a half-day holiday tomorrow, I’ve planned everything: we’ll leave the children with the neighbours and go out in the evening.’ After a long silence Feroza said, ‘I haven’t been out in such a long time. I know you don’t have the time, so I don’t tell you, but sometimes it feels so terrible being cooped up at home all day. I’ve forgotten the last time I went out… We really are going out tomorrow, aren’t we?’ Alam smiled. ‘We are. You decide where.’ Tilting her head in thought, Feroza said, ‘I’ll think it over and tell you.’ Some time passed. Feroza pulled Alam up by the hand. ‘Come.’ Alam did not budge. ‘Let’s stay here, it’s such a beautiful night.’ But when he turned round to catch Feroza’s eyes, he laughed. ‘I see, all right, let’s go.’

The next morning Alam woke up the usual way. Sunshine poured in through the window onto the mosquito net, making a part of its grimy surface gleam with gold. The two sparrows that had nested in the room flew off. The bedclothes had large holes. Counting them, Alam got off the bed. On his way to the tap in the yard with his toothbrush, he caught a glimpse of Feroza at the kitchen door. Turning at the sound of his footsteps, she smiled. So did Alam, remembering yesterday. They were looking at each other afresh after a long time. Last night’s memories were as alive as the days after their wedding. Thank goodness they had had this fight after all this time.

Alam got busy again after brushing his teeth. Today he was free of the ration-shop chore, but the time just flew as he finished his breakfast and did the daily shopping. Before going in for his bath he cleaned the motorbike thoroughly with a rag and oil, washing the wheels and the mudguard carefully. It had been backfiring a great deal lately, and giving off sparks whenever he accelerated – not even the mechanics at the workshop had succeeded in fixing these. When he was done with his bath he made Noton and Toton ride pillion and took them to school. Being a half-day, he came home with them at lunchtime. When she had put the dishes away after lunch, Feroza lay down next to him in the bedroom. She said, ‘Do you know where I’ve planned for us to go?’ When Alam looked at her blankly, she said, ‘Nowhere. We won’t go to the park or for a film. You know what we’ll do? I’m just going to sit behind you on your motorbike, and ride with you on the streets. Let’s see how far you can take me.’ Alam said confidently, ‘All right, I’ll take you to places that will amaze you.’ Feroza nodded. ‘Of course you will. Do you know how long it’s been since I went out? The entire city must have changed.’ Alam said softly, ‘That’s true, I know what you’re saying, but where’s the time – between the shopping, ration shop, school and office the day’s over before you know it. In fact, it’s going to be my first time out too, for a long time!’

The first part of the afternoon was spent in conversation. Feroza didn’t move her hand from Alam’s hair. They got out of bed in a while to dress. When Feroza put on an old sari she had pulled out of a trunk, Alam stared at her in wonder. ‘You really are beautiful… How’s your mother looking, Noton?’ Calling the children, Feroza said, ‘Babies, we’re going out for a bit, will you wait for us at Ranju’s house? We’ll bring chocolate.’

The children nodded. Alam locked the front door and put the keys in his pocket. Noton and Toton waved from the neighbour’s veranda. Alam said, ‘Can you believe how long it’s been? You’re right, Feroza, we won’t go any place in particular, we’ll just drift.’

Alam accelerated as soon as they turned the corner, telling Feroza, ‘We’ll go wherever the motorbike takes us.’ They passed the ration-shop a little further ahead. He pointed it out to Feroza, ‘That’s where we get our rations… and there’s the bazaar…’ He showed her where it was, adding, ‘It isn’t crowded now, but if only you could see it in the morning…’ Alam increased his speed, his voice jovial. Then he slowed down on spotting the children’s school in the distance, stopping abruptly in front of it. ‘Do you know what this is? No, mustn’t check the signboard, this is where Noton and Toton go to school.’ He set off before Feroza could take a good look. Alam wasn’t thinking much about the route, the motorbike seemed to have a mind of its own. When they went up to his office, he stopped the motorbike with a flourish. ‘Do you know where we are now?’ Feroza shook her head like a little girl. ‘How should I know, though I can make a guess…?’ Alam said forcefully, ‘Right, guess. You see that room to the west with the blue window, that’s where we work.’ They proceeded further up the road. Alam steered the motorbike though the people, the traffic, and the potholed roads with consummate ease. ‘Now, here you are,’ he said. ‘This is where I get the motorbike repaired, Nibedita Workshop, I know some of the mechanics here, do you want to meet them?’ ‘Boring!’ said Feroza. The motorbike moved on. ‘I’ll show you something interesting now,’ said Alam, ‘See that single-storeyed yellow house on the right? Do you know whose that is? That goddamned moneylender Hannan! He works with us. Whenever I need some money I borrow it from him. He charges a lot of interest, that’s true, but then who lends money nowadays?’

Feroza had put one hand on Alam’s shoulder, balancing herself by clutching her seat with the other. She had often heard Alam talk of these places, but she was seeing them for the first time today. She assumed they’d go further ahead now. Alam accelerated, but was forced to slow down when sparks started to appear. A little later, the roads began to appear familiar to Feroza. As they continued, Feroza spotted their house, perhaps she even caught a glimpse of Noton in the neighbours’ veranda. And then, in succession, they passed the ration-shop and the bazaar swamped by a sea of mud and filth. She told Alam, ‘How come you took the same road, we’ve been here already.’ ‘Really?’ said Alam, only to be surprised himself. ‘You’re right, I wasn’t paying attention.’ By then they had gone past the children’s school. Feroza assumed they’d turn in a different direction now. Alam was looking completely unperturbed. But a little later, there they were, Alam’s office, then Nibedita Workshop, and, further on, Hannan the moneylender’s house. Feroza was annoyed now. ‘Is this a joke! Are you going to take me round and round on the same road?’ Keeping a close eye on the engine, Alam said: ‘We’ll take a different road now, I don’t know what happened there, I took the same route without realising it.’

A short while later Feroza practically screamed. The motorbike was back in front of their house. Then it sped past the ration-shop towards the bazaar. Feroza said grimly, ‘Let me off, there’s no need for all this drama. Don’t you know any other road?’ But she could feel Alam trembling under the hand she had put on his shoulder. ‘No,’ he said. ‘Wait, Feroza, let me try.’ He bent low over the motorbike, looking at the road through narrowed eyes, changed gears repeatedly and meaninglessly, accelerated and then slowed down. But the motorbike kept going, past the bazaar and the ration-shop, a little further on the children’s school became visible, then Alam’s office, Nibedita Workshop. Alam tried his best, tinkering with different parts. Feroza couldn’t understand any of it; all she could make out was that Alam was trembling uncontrollably. She realised that they were on the same road again, Alam’s hands on the handle shook, he shouted, ‘I’m trying, Feroza, I’m trying, but I can’t get out, Feroza, the bazaar and the ration-shop and the school and the office and the workshop and Hannan’s house – I can’t get out, I can’t get out, Feroza.’

*Jaggery: a traditional cane sugar, consumed in Asia and Africa; the concentrated product of date, cane juice or palm sap.

Moinul Ahsan Saber studied Sociology at the University of Dhaka and was the editor of the popular weekly magazine, Shaptahik 2000, before turning to writing full time in recent years. He first came into the limelight following the publication of his debut collection of short stories, Porasto Sahish in 1982. Since then, he has written numerous novels and stories, including those for children. Saber’s work has received, among others, the Philips Literary Award, Bapi Shahriar Children’s Award, Humayun Qadir Literature Award, BRAC Bank Samakal Shahitya Puroshkar and Bangla Academy Shahitya Puroshkar.

Masrufa Ayesha Nusrat is a literary translator who teaches English at the East West University in Dhaka. She was educated in Bangladesh and the UK. Nusrat recently published Celebration & Other Stories, a collection of her own translations of short stories by contemporary women writers of Bangladesh.

The Raincoat - Akhteruzzaman Elias

The Weapon - Syed Manzoorul Islam

The Decision - Parvez Hossain

Mother - Rashida Sultana

The Circle - Moinul Ahsan Saber

Home - Shaheen Akhtar

The Princess and the Father - Bipradash Barua

Helal was on his Way to Meet Reshma - Anwara Syed Haq

The Path of Poribibi - Salma Bani

The Widening Gyre - Wasi Ahmed

গল্পগুলি অনুবাদ করেছেন Pushpita Alam, Arunava Sinha, Syeda Nur-E-Royhan, Masrufa Ayesha Nusrat, Arifa Ghani Rahman, Mohammad Shafiqul Islam, Marzia Rahman, Mohammad Mahmudul Haque, Ahmed Ahsanuzzaman.

এই বইয়ের একটি গল্প আমি পাঠকদের জন্য তুলে দিচ্ছি। আশাকরি গল্পটি পড়বেন, এবং বুঝতে পারবেন ছোটগল্প রচনায় আমাদের দেশের গল্পকারেরা কত শক্তিমান।

বইটি আমাজনে কিনতে হলে এইখানে ক্লিক করুন।

ঢাকায় প্রথমার দোকানে, পাঠক সমাবেশে খোজ করুন।

বৃত্ত

মঈনুল আহসান সাবের

মশারির একদিক উঠিয়ে ফিরোজা নেমে গেছে ভোর হওয়ার সঙ্গে-সঙ্গে। নেমে যাওয়ার আগে তাকে একবার ঠেলেছিল আলমের খেয়াল আছে। তার ঘুম ভাঙাল দুটাে চড়ুই পাখি। রোদ পুরো জানালা গলিয়ে এসেছে ঘরের ভেতর। রোদ পড়ায় ময়লা মশারির একাংশ অতি উজ্জ্বল। চড়ুই, পাখি দু’টাে থেকে চােখ সরিয়ে সেদিকে কতক্ষণ তাকিয়ে থাকে সে। ছেলে দু’টাে পড়ছে বারান্দায় বসে। মশারির মধ্যে উঠে বসতে-বসতে সে বারান্দায় বড়টির মাথা সামনে-পেছনে দুলছে দেখতে পায়। শরীরের আড়মোড়া ভাঙতে সে অনেক সময় নেয়। সারাটা দিনের মধ্যে এই সামান্যক্ষণটুকুই আনন্দের। এইটুকু সময় সে নিজের ইচ্ছেমতো ফুরাতে চায়। একবার বিছানা ছেড়ে ওঠার পর আর কোনও ফুরসৎ নেই। বিছানা ছেড়ে সামনের দেয়ালে বাধানো ছোট স্নান আয়নায় নিজেকে দেখে একপলক । কোনও দুঃখ ঘাই খেয়ে ওঠার আগেই সে চোখ সরিয়ে নেয়। কিন্তু ওই একপলকের মধ্যেই অনেক কিছু ধরা পড়ে গেছে। দু'চােখের নীচে কালি, গাল ভেঙে গেছে, ছেড়া ময়লা গেঞ্জি । আয়নার সামনে দাঁড়িয়ে মাথা নীচু করে ব্ৰাশে পেস্ট নিতে-নিতে সে আপন মনে হাসে।

রান্নাঘরের পাশে কলতলায় বসার সময় ফিরোজা তাকে একপলক দেখে। আলম তাকে বড় ভালোবাসে। বিয়ের পর দশবছর ধরে শুধু ক্লান্তি বেড়েছে, ভালোবাসার অনেক কিছুই সে ফিরোজাকে দেখাতে পারেনি। কলতলা এই গ্ৰীষ্মের দিনেও কাদায় একাকার। কোথাও কালচে শ্যাওলা প্রায় জমে উঠেছে। ক্ষয়ে যাওয়া দেয়ালে নোনা আস্তর; ফেটে যাওয়া সিমেন্ট বাধাইয়ের ফাঁক-ফোকর গলে বেরিয়ে এসেছে চারাগাছ। আরও একটু সামনে বেশ বড় একটা গাছ। কলতলায় বসলে সেই গাছের কালো-কঠিন গুড়ি পর্যন্ত নজর চলে। আলম এসব দেখতে-দেখতে মুখ ধুয়ে নিল। ততক্ষণে ফিরোজার নাস্তা তৈরি শেষ। আটার রুটির সঙ্গে ভাজি কিংবা গুড়, গতরাতের তরকারি থাকলে তার কিছু। পেছনের বারান্দায় যে-দিকটায় সকালের রোদ এসে পড়েছে সেখানে পুরনাে একটা ছােট টেবিল। তারা চারজন কোনওমতে বসে। কতকিছু আলগা হয়ে গেছে দশ বছরের অভাবের সংসারে । কিন্তু এই দীর্ঘদিনেও নিয়মটা ভাঙেনি আলম, এসময় ফিরোজা তার পাশে বসবেই। নাস্তার এই সামান্য সময়টুকুয় ক্ষণিকের জন্যে হলেও একটা বন্ধন গড়ে ওঠে। আর ফিরোজা পারেও বটে। একটু পরেই কাজের চাপ বেড়ে যাবে তাই এই সময়টুকু মাতিয়ে রাখে সে। নোটন-টােটনকে নাস্তা এগিয়ে দিয়ে সে আলমকে বলল-আজকে অফিসে যাওয়ার আগে তোমার কী-কী কাজ, জানো? আলম খুব গম্ভীর হয়ে মাথা নাড়ে, না তো। তবে শোনো ফিরোজা আঙুল ওঠায়, এক, বাজারে যেতে হবে, দুই, রেশন আনতে হবে, তিন, নোটন-টােটনকে স্কুলে পৌঁছে দিতে হবে । আলম মাথা নোয়ায়, জো হুকুম, হয়ে যাবে। রেশন সপ্তাহে একদিন, বাকি কাজ দুটো রোজাকার। কিন্তু প্ৰায় এইভাবে প্রতিদিন আরম্ভ করে তারা।

নাস্তা শেষ করে বাজারের ব্যাগ হাতে বের হতে-হতেই এই আনন্দের রেশটুকু চলে যায়। পয়সা খরচ করার ক্ষমতা তার কত কম-রোজ এসময় তার মনে পড়ে যায়। বাজার বাড়ির সামান্য দূরে। এটা একটা বড় সুবিধা, নইলে বাজার থেকে ফিরেই তাকে অফিসে ছুটতে হত। অনেক সময় নষ্ট হয় বাজারে । এক জিনিসের দাম বহুবার জিজ্ঞেস করে আবার ঘুরে-ফিরে আসে। কেনার ইচ্ছেটুকু বাদে আর কোনও ক্ষমতা নেই তার—এই চিন্তা খুব ক্ৰোধ জাগিয়ে দেয়। কিন্তু কিছু করার নেই, কম পয়সায় পচা-বাসি জিনিস কিনে সে বাড়ি ফিরে আসে। তখন বসবার সময় নেই। সে বাজারের ব্যাগ নামিয়ে রেখে রেশনের ব্যাগ-কার্ড নিয়ে বেরিয়ে যায়। রেশন দোকানে লম্বা লাইন। তার মতো অনেক অফিসযাত্রীরা লাইনে। এই সামান্য সময়েই লাইনের মধ্যে দ্রব্যমূল্য, রাজনীতি, সামাজিক অবক্ষয় বাদামের খোসার মতো ভেঙে-ভেঙে যায়। তার সময় আসতে দেরি হয়। বাড়ি ফিরে সে গোসল সেরে নেয়। তাড়াতাড়ি। এখনও পৌনে এক ঘণ্টা বাকি অফিসের । বহুদিনের অভ্যেসে সে এসব ব্যাপারে অত্যন্ত অভ্যস্ত। ঘড়ির কাটার সঙ্গে তাল মিলিয়ে এগোয়। অফিসে পৌছতে দেরি হয় না। সে গোসল সেরে বারান্দার তারে কাপড় মেলে দিতে-দিতে দেখে নােটন-টােটন স্কুল-ড্রেস পরে খাবার টেবিলে বসে গেছে। খুব তাড়াতাড়ি খেতেও পারে আলম। ফিরোজা প্রতিদিন বারণ করে--দুটাে মিনিট দেরি হােক অফিসে, এমন কিছু এসে যাবে না, তুমি ভাত মাথায় তুলছ কেন?

ভাত বেড়ে দিতে-দিতে ফিরোজা বলে—তুমি বড় শুকিয়ে গেছ, দিনরাত এত খাটছি। অভাব আর ক্লান্তির নীচে কত ভালোবাসা চাপা পড়ে গেছে, এইসব মুহূর্তে তা ঘাই খেয়ে ওঠে । এ-জন্যেই ফিরোজাকে বড় ভালো লাগে আলমের। খুব একটা ভেবে চিনতে বলেনি হয়তো ফিরোজা, আর এটুকু বলা ছাড়া আর কিছু করার নেই ফিরোজার, কিন্তু আন্তরিকতাটুকু টের পায় আলম। এ-সময় একসঙ্গে খেতে বসে না ফিরোজা। তার অনেক কাজ। চুলোর আগুনে তেতে-যাওয়া-মুখে ভাত বেড়ে খাইয়ে আলম আর নোটন-টোটনকে বিদায় করে সে ঘর গুছাবে, বাকি রান্না সারবে, কাপড় ধোবে, এভাবে তার সারাটা দিন চলে যায়। দুপুরের পর-পর ফিরে আসে নোটন-টােটন, সন্ধ্যার আগে-আগে আলম।

আলমের একটা পুরনাে মোটরসাইকেল আছে। বিয়ের পরপরই ধার করে কিনে ফেলেছিল। এখনও খুব কাজ দিচ্ছে। মোটরসাইকেলটা গত পরশু ওয়ার্কশপে দিয়েছে; আজকাল প্রায় ট্রাবল দেয়। চেনা-জানা ওয়ার্কশপ বলে মাসের মধ্যে দু-তিনবারও অল্প খরচে সারিয়ে নিতে পারে। নোটন-টােটনকে স্কুলে পৌছে দিয়ে সে অফিসে যাবে। দরজায় দাঁড়ানো ফিরোজার কাছ থেকে বিদায় নিয়ে তারা রাস্তায় নামে।

আলম একটা রিকশা নেয়। রিকশা নেয়া তার পোষায় না। কিন্তু মোটরসাইকেল নষ্ট, এই অফিস আওয়ারে বাসের জন্যে দাড়ানো ও অর্থহীন-আলম এইসব ভেবে ব্যাপারটা চুকিয়ে ফেলে।

রিকশা থেকে নেমে ভাড়া চুকিয়ে আলম সেখানেই দাঁড়িয়ে থাকে। নােটন-টােটন স্কুলের গেট পেরিয়ে ভেতরে অদৃশ্য হয়ে গেলে সে ফুটপাতে উঠে এল । এখনও পনের মিনিট বাকি অফিস আরম্ভ হওয়ার । এই সময়ের মধ্যে হেঁটে সে দিব্যি পৌছে যাবে।

অফিসে পাঁচ-দশ মিনিট দেরি হলে কোনও ক্ষতি নেই। কোনও জবাবদিহির সম্মুখীন হওয়ারও ভয় নেই। অন্য অনেকের এ-রকম পাঁচ-দশ মিনিট দেরি হরদমই ঘটছে। অফিস ছুটি হওয়ার আগে বেরিয়ে পড়াও চলে। কিন্তু আলম পারে না। ঠিক সময়ে অফিসে পৌছানো এক শক্ত রুটিনের মতো হয়ে দাঁড়িয়েছে। অত নৈতিকতার ধার ধারে না সে, এ-কথা ঠিক, অফিসে ঠিক সময়মতো না-পৌছলে ফাকি দেয়া হবে এ-কথাও তার মনে আসে না। কিন্তু সময়মতো অফিসে পৌছানোর রুটিনটুকু সে এড়াতে পারে না ।

অফিসে তখন যারা এসেছে তারা নিজেদের চেয়ারে বসে গল্পে ব্যস্ত। আসিফ ছোকড়া অল্পদিন হল পেছনের দরোজা দিয়ে চাকরিতে ঢুকেছে। নিজের দায়-দায়িত্ব ছাড়া কাঁধের ওপর আর কোনও চাপ নেই, তার গলা রোজকার মতো আজকেও জোরাল শোনাচ্ছে। নিজের চেয়ারে বসে রুমালে মুখ মুছে সামান্যক্ষণ কান পাতল সে, আসিফের দেখা গতকালের বিদেশী সিনেমার গল্প। একটু পরেই এ গল্প চাপা পড়ে যাবে সে জানে। রোজকার ব্যাপার। এরপর জিনিসপত্রের দাম, বিশ্ব রাজনীতি, রাস্তা-ঘাট, হাসপাতাল কিংবা যাতায়াত ব্যবস্থার দুরবস্থা, বাসের ভিড়, মুদ্রাস্ফীতি, রিকশাআলাদের অভদ্রতা ক্রমান্বয়ে ঘুরে-ফিরে আসবে।

সারা সকালে জুড়ে কী ক্লান্তি জড় হয়েছে, চেয়ারে শরীর এলিয়ে দিলেই সে টের পায়। ব্যাপারগুলোর একটাও তার পক্ষে এড়ানো সম্ভব নয়। বাজার, রেশন, নোটন-টােটনকে স্কুলে নিয়ে আসা, বাসায় নিয়ে যাওয়া সব তাকেই করতে হবে। কিন্তু এই সামান্য বিশ্রামের সময় ক্লান্তি সারা শরীরে ছড়িয়ে পড়লে সে বুঝতে পারে, কী দ্রুত সে নিজেকে ক্ষয় করে ফেলছে। সামনে রাখা গতকালের অসমাপ্ত ফাইল টেনে নিয়েও সে মন থেকে কথাগুলো ঝেড়ে ফেলতে পারে না। কী দ্রুত ফুরিয়ে যাচ্ছে সময়, তার আগে কী দ্রুত ফুরিয়ে গেছে তার যৌবন। ফিরোজার ভালোবাসাটুকু তাকে ধরে না রাখলে সে সব ছেড়ে এতদিনে হাঁটতে-হাঁটতে সেই কোথায় চলে যেত। এই একঘেয়ে জীবন, মাঝে-মাঝে কী একটা ভীষণ ইচ্ছে করে চিৎকার করে ওঠার। অথচ সে-জন্যে প্রয়োজনীয় সাহস আর শক্তিটুকুও তার নেই। তার আর ফিরোজার সময় পেরিয়ে গেছে, মাত্র দশবছর পরেই এ-রকম মনে হয়, কিন্তু এই চিন্তার মধ্যে বুদ্বুদের মতো জেগে ওঠে দুঃখ-মাত্র দশবছরেই ফুরিয়ে গেলাম! অভাব আর ক্লান্তির খোলস ক্রমশ পুরু হয় আর গায়ের সঙ্গে আরও সেঁটে বসে। খুব একটা ইচ্ছে করে হঠাৎ করে কিছু করে বসার, একটা ভীষণ রকম অনিয়মের। কিন্তু হঠাৎ করে একটা সাধারণ ফ্যামিলি পিকনিক কিংবা একদিন শখ করে বড় হােটেলে খাওয়া-এই আয়াসসাধ্য কাজগুলোও হয়ে ওঠে না। সে টের পায়, এসব তার পক্ষে আর সম্ভব নয়। হঠাৎ করে করে ফেলার সাহসটুকুও যদি তার থাকত!

লানচের সময়টুকুতেও অবসর নেই। নোটন-টােটন স্কুলের গেটে দাঁড়িয়ে থাকবে ছুটির পর । এ-সময় লাঞ্চের পরও দশ-পনের মিনিট নিদ্বিধায় চুরি করে আলম। নোটন-টোেটনকে স্কুল থেকে নিয়ে বাসায় পৌছে খেয়েদেয়ে সময়মতো অফিসে ফেরা সম্ভব নয়। নোটন-টােটন স্কুলের গেটে দাঁড়িয়ে ছিল। আলমকে দেখে এগিয়ে আসে। এ সময় তাদের বাড়ির দিকের কিছু খালি বাস পাওয়া যায়। বাসায় ফিরে আরেকবার গোসল সারে আলম। বাথরুম থেকে সে চেঁচায় ছিল—ফিরোজা খাবারের কতদূর? দু'এক ঘণ্টা লাগবে আরও—ফিরোজা উত্তর দেয়। আলম বের হয়ে দেখে টেবিলে খাবার তৈরি । নোটন-টোটন কালতলাতেই গোসল সেরে নিয়েছে। নোটন বলে-বাবা জানো, আজকে ক্লাস টেস্টে আমি ফাস্ট হইনি। আলম বলে---সামনের বার হােয়ো, হবে তো? নোটন মাথা নাড়ে ।

সিগারেট খায় না আলম । খাওয়ার পর এক খিলিপান এগিয়ে দেয় ফিরোজা । এখান থেকে বাস-স্ট্যান্ড সামান্য দূরে। সোজাসুজি রাস্তা হলে ফিরোজা তাকে বাস-স্ট্যান্ডে দেখতে পেত। কিন্তু রাস্তা বাঁক নিয়েছে। এই বাঁকে এসে একবার ফিরে তাকায় আলম। ফিরোজা এই দশবছর পরেও দরোজায় দাঁড়িয়ে । হঠাৎ করে হাত নাড়ার ইচ্ছে জাগে আলমের। চারপাশে তাকায় সে, কেউ দেখছে না দেখে সামান্য হাত তোলে। ফিরোজা বোধ হয় বুঝতে পারে না, কিংবা লজ্জা পায়, কিন্তু পাশে দাঁড়ানো নোটন-টােটন দু’হাত তুলে নাড়ে।

দিন দুই পর অফিস ছুটি হলে আলম ওয়ার্কশপে যায়। তার মোটরসাইকেল ঠিক হয়ে আছে। পরিচিত মিস্ত্রি বলে-আলম বাই, যন্ত্রটা বেঁচি দেন। আলম মাথা নাড়ে-হু, তুমি বললে আর আমি বেচে দিলাম, যে সার্ভিস দিচ্ছে। মিস্ত্রি বলে-নতুন একটা কিনি লন। আলম বলল-টাকা তুমি দেবে? মিস্ত্রি তখন হাসে।

বাড়ি ফিরে সে দেখতে পায় ফিরোজা শাড়ি-ব্লাউজের কাপড়ের ফেরিঅলাকে দরোজায় ডেকে শাড়ি উল্টে-পাল্টে দেখছে। পাশে দাড়ানো নোটন-টোটনের উৎসাহ আরও বেশি। এই দৃশ্যটাই হঠাৎ মন খারাপ করে দিল আলমের। এ-সময় শাড়ি-অলাকে কেন ডেকেছে ফিরোজা? এ-সময় এসব কেনাকাটা সম্ভব নয় ফিরোজা এই দশবছরে টের পায়নি? এসময় নিজের অক্ষমতাটুকুও টের পায় আলম, তার রাগ আরও লাফিয়ে উঠে। সে আর একবারও সেদিকে তাকিয়ে দেখে না। মােটর-সাইকেল রেখে উদাসভাবে ভেতরে ঢুকে যায়। ফিরোজা তার দিকে তাকিয়ে ঠোঁট টিপে হাসছে, সে বুঝতে পারে, কিন্তু সে প্রশ্রয় দেয় না। শোবার ঘরে বসে জামা-কাপড় পাল্টানোর পর খুব পুরনো একটা পত্রিকা দেখতে-দেখতে বাইরে সে সামান্যক্ষণ মৃদু কথাবার্তা শোনে । ফিরোজা কতক্ষণ পর ঘরে ঢোকে । আলম ভাবে টাকার কথা বলবে এখন । কিন্তু ফিরোজা পাশে বসে বলে-তুমি অত গম্ভীর কেন? আলম কথা বলে না। ফিরোজা আবার বলে—কী হল, কথা বলছ না কেন? আলম পত্রিকা থেকে চােখ তোলে না— শাড়িঅলা ডেকেছিলে যে বড়, পয়সা কোথায়? ফিরোজা হেসে ফেলে-বারে, আমি কিনলাম নাকি!

কেনার জন্যেই তো ডেকেছিলে । পছন্দ হল না। তাই কিনলে না | পছন্দ হলে কিনতে না? এ-সময় এতগুলো টাকা ।

ফিরোজা রাগে না-কে বলেছে তোমাকে আমি কিনতাম, পাগল, আমি শুধু দেখলাম ।

কিনবে না তো ডেকেছিলে কেন?

আহা, বললামই তো দেখতে, আমি শাড়িগুলো দেখলাম, দরদাম জিজ্ঞেস করলাম-ব্যাস আর কিছু নয়।

আলমের রাগ এরপর কমে যাওয়া উচিত ছিল, কিন্তু সে উল্টো চেচিয়ে উঠে-তুমি তো জানোই এ-সময় শাড়ি কেনা সম্ভব নয়, তবু ডাকবে কেন?

বারে, না-হয় নাই কিনলাম, তাই বলে দেখতেও পারব না?

না।

কেন?

এ-সময় সামান্য উষ্মা উঠে আসে ফিরোজার কথার সঙ্গে ।

অত কথা কেন, আমি বলছি তুমি কিনবে না-ব্যাস।

খুব শান্ত গলায় ফিরোজা বলে-শেষ শাড়িটা কবে কিনে দিয়েছে তা তো ভুলেই গেছি, শুধু দু’একটা শাড়ি দেখব তাও তুমি দেবে না?

এ-সময় তোমার শাড়ি কেনার শখ হওয়াও উচিত নয় ।

কেন-ফিরোজা এবার চেচিয়ে ওঠে-কোন শখ হবে না, ক’টা শাড়ি তুমি কিনে দিয়েছ আমাকে?

আমার কাটা জামা-কাপড় তুমি জানো?

আমি বলছি তোমার অনেক বেশি, কিন্তু আমার যা থাকা উচিত ছিল তার অর্ধেকও নেই।

ও-রকম খোটা দিও না। নেই তো নেই, এখন কী করতে হবে?

কী করবে। আবার, কিনে দেওয়ার মুরোদ নেই, আমার যা ইচ্ছে করব।

চুপ-আলম চেচায়-বেহায়া মেয়ে, আমি সারাদিন কী খাটছি পাগল হওয়ার দশা, অফিস থেকে ফিরতেই তুমি বকবক আরম্ভ করলে? -

আরম্ভ তাে করলে তুমি, আর শুধু তুমিই খাটছ, আমি কিছু করছি না? সারাদিন আমি পায়ের ওপর পা তুলে বসে থাকি?

সে-রকমই তো । তুমি কী জানো আমার কী খোজ রাখো, বাজার রেশন, নোটন-টােটনকে স্কুলে পৌছে দাও, বাসায় নিয়ে আসো; তার ওপর অফিসে একগাদা কাজ। তুমি কোনওদিন এসব নিয়ে আমাকে কিছু বলেছ?

বলিনি না, তুমি বলছ আমি বলিনি, বেশ তুমি আমার জন্যে কী করেছ, তুমি কবে আমাকে বেড়াতে নিয়ে গেছ, সারাদিন এত কিছুর পরেও এই অন্ধকার ঘরে পড়ে থাকি, কোনওদিন তো বলনি-চল বেড়িয়ে আসি, তুমি কোন খোজটা রাখো আমার মনের?

আলম সে-সব কথা উড়িয়ে দেয়-আরে রাখো, আমন আলগা ফ্যাচফ্যাচ করো না।

ফিরোজা আর কথা বাড়ায় না। ঘর ছেড়ে বেরিয়ে যাওয়ার আগে চৌকাঠে একবার থামে, আঁচলে চােখ মােছে। সন্ধ্যার আগে নােটন-টােটন সামনের ছােট মাঠ থেকে ফিরে হাত-মুখ ধুয়ে পড়তে বসে। আলম সে-ঘরেই বসে থাকে, সেই পুরনো পত্রিকাই উল্টেপাল্টে পনেরবার দেখে। সন্ধ্যার পর ফিরোজার আওয়াজ পাওয়া যায় রান্নাঘরে। তবে বোধ হয় রাগ করেনি- আলমের মনে হয়। অর্থহীন এক ঝগড়া বাঁধিয়ে ফেলেছে সে; এখন বেশ বুঝতে পারছে। তবে ফিরোজা এখন রান্নাঘরে, তবে ফিরোজা রাগ করেনি—এ-রকম মনে হতেই আলম বেশ উৎফুল্ল বোধ করে। নিজের দোষ আর লজ্জাটুকু ভোলার জন্যে সে আরও কতক্ষণ অপেক্ষা করে। পত্রিকাটা হাতে নিয়েই সে আস্তে-আস্তে রান্নাঘরের দরোজায় এসে দাড়ায়। ফিরোজা মুখ খুব নিচু করে চাল বাছছে। আলম আস্তে ডাকে-ফিরোজা। একটু চমকে উঠেছিল ফিরোজা, ডাকটা আলমের বুঝতে পেরেই শক্ত হয়ে যায়। আলম আরও একটু এগিয়ে যায়, পাশে বসবে কি বসবে না ভাবে, দাঁড়িয়ে থেকেই বলে।--তুমি রাগ করো না ফিরোজা, অফিস থেকেই হঠাৎ মন খারাপ, কথা বলবে না ফিরোজা ? ফিরোজা মাথা গুজে থাকে, কোনও সাড়া-শব্দ করে না, চাল বাছা হাতও আগের মতো দ্রুত চলছে না। আলম আবার ডাকে । ফিরোজা ঝট করে মুখ ফেরায়, কিন্তু কথা বলতে সময় নেয়—তুমি কথা বলো না আমার সঙ্গে, যাও । খুব কেঁদেছে ফিরোজা, দু'চোখ খুব লাল, এখনও জলের পরল পড়ে আছে। ফিরোজার কথা শুনে একটুও রাগে না আলম, ভেজা লাল দু'চোখ দেখে সে দমে যায়। নিজের অন্যায় বোধটুকু আবার তার জেগে ওঠে । এখন হবে না বুঝতে পেরে সে রান্নাঘর থেকে সরে আসে।

ফিরে এসেও তার ভালো লাগে না। কতক্ষণ নোটন-টোটনের বই-খাতা উল্টেপাল্টে দেখে । শেষে ঘর ছেড়ে রাস্তায় নেমে ঘুরে বেড়ায় । বাসস্ট্যান্ডের উল্টোদিকে একটা মাঠ আছে। সেখানে গিয়ে বসে থাকে। মাঠে অনেক লোকজন বাতাস গায়ে মেখে গল্প করছে। আশেপাশে কখনও বাদাম অলা, এই রাতেও কখনও আইসক্রিম, কখনও দু’একজন সন্দেহজনক লোক । সে মাঠের এককোণে হু-হু বাতাসের মধ্যে বসে থাকে। চারপাশের হইচই সে লক্ষ্যই করে না। মাথা গুজে বসে থাকতে-থাকতে হঠাৎ তার কান্না পায়। সে খুব চেষ্টা করে রুখে রাখার। এই বয়সে কান্না, তার লজ্জা লাগে । স্বামী-স্ত্রীর এ-রকম ছোটখাটাে ঝগড়া হবেই, তার জন্যে কাঁদবে কেন সে? কিন্তু ক্রমশ সে বুঝতে পারে শুধু আজকের বিকেলের ঘটনার জন্যে তার কান্না পাচ্ছে না, আসলে অনেকদিন ধরে তার কাঁদতে ইচ্ছে করছে, অনেকদিন ধরে কান্না তৈরি হয়েছে তার ভেতর । সব এখন বেরিয়ে যাবে বলে উঠে আসছে গলা ছাড়িয়ে । বাতাসের মধ্যে সে কেঁপে ওঠে ।

বহুক্ষণ পর চোখ তুলে সে দেখল মাঠ অনেক ফাঁকা। লোকজন, বাদাম অলা প্ৰায় সবাই চলে গেছে। নিজেকে খুব হালকা মনে হল তার। কত দুঃখ তার একসঙ্গে কুণ্ডলী পাকিয়ে উঠে চলে গেছে। তখন শুধু ফিরোজার প্রতি সামান্য অভিমান । রাত হয়েছে সে বুঝতে পারে। ফিরোজা আর নোটন-টােটন বাড়িতে একা, সে উঠে বাড়ির দিকে পা বাড়ায় । বাসস্ট্যান্ডের আগের বাকিটা ঘুরলেই সে বাড়ির দরোজা দেখতে পায়, একপাশে এক মূর্তি দাঁড়িয়ে আলো-ছায়ায়। আলম ক্রমশ আরও এগোলে সেই মূর্তি দরোজা থেকে সরে যায়। ঘরে ঢুকতেই পাশের ঘরের জানালায় মুখ এনে নোটন বলে-আমরা সবাই খেয়েছি, মা বলেছে তােমাকে খেয়ে নিতে। আলম দ্বিরুক্তি করে না। ফিরোজার দৃষ্টি আকর্ষণের কোনও চেষ্টা না-করে সে খেয়ে নেয়। নিজেই বাসন-কোসন গুছিয়ে রাখে । শেষে পেছনের বারান্দার এককোণে চেয়ার টেনে বসে পড়ে। অনেক দিন পর রাতের আকাশের দিকে চোখ পড়ে তার। আকাশে অনেক তারা, পশ্চিম দিকে একটু হেলে পড়া সম্পূর্ণ চাঁদ। সামনে যে বড় গাছ, বাতাসে তার পাতার আওয়াজ পাওয়া যাচ্ছে। ভেতরের দু’ঘরের আলো নিভে গেছে। ফিরোজা কি শুয়ে পড়েছে, ভেবে তার আরও অভিমান হয়। তার ঘুম পাচ্ছে, কিন্তু ফিরোজার পাশে গিয়ে সে এখন কীভাবে শোবে ভেবে তার লজ্জাও করছে। এ-সময় ফিরোজা বারান্দায় আসে। পেছনে দরোজায় মৃদু আওয়াজ হতেই সে চোখ ফিরিয়ে দেখে ; ফিরোজা তার পিছনে এসে দাঁড়ায় । আলম চুপ করে কালো-কঠিন গাছের দিকে তাকিয়ে থাকে। ফিরোজা বলে—শোনো, তুমি আমার সঙ্গে বিকেলে ঝগড়া করলে কেন?

আশেপাশে কারও জেগে থাকার কোনও সাড়াশব্দ নেই। আলম নাগালের মধ্যে দাঁড়ানো ফিরোজাকে ঝটিতি টেনে এনে উদভ্ৰান্তের মতো চুমু খায়। চুম্বনের পূর্বমুহূর্ত পর্যন্ত শক্ত ছিল ফিরোজা, পরমুহূর্তে সে উদভ্ৰান্ত না-হলেও সহজ হয়ে ওঠে। পরে সে আলমের মাথায় হাত রেখে উঠে দাঁড়ায়, বলে-আমার খুব খারাপ লেগেছিল, তুমি তো কখনও আমাকে ওভাবে বলো না । আলম বোকার মতো মাথা নাড়ে-হঠাৎ করে ফিরোজা, হঠাৎ করে এমনিতেই মনটা খারাপ হয়ে গেল, তোমাকে শাড়ি দেখতে দেখে আমার মনে হল বহু আগেই তোমাকে একটা নতুন শাড়ি দেয়া উচিত ছিল আমার, কিন্তু অতটুকু পয়সাও অনেকদিন হাতে জমছে না খেয়াল হতেই তোমার ওপর রেগে গেলাম। আসলে আমি তোমার ওপর একটুও রাগ করিনি। একটু থেমে সে বলে—তুমি খুব কষ্ট পেয়েছ না? ফিরোজা কথা বলে না, সে আলমের চুল মুঠো করে চেপে ধরে আবার ছেড়ে দেয়। আলম বলে---সামনের মাসে তোমাকে একটা সুন্দর শাড়ি কিনে দেব, আমি কিনে দেব পছন্দ করে। ফিরোজা মাথা নাড়ে--উহু, আমার তো টাকা নেই, তুমি আমাকে টাকা দিও, আমি তোমাকে শার্টের কাপড় কিনে দেব পছন্দ করে। না, সামনের মাসে শাড়ি কেনা হবে, আলম আবার ফিরোজাকে কাছে টেনে আনে, আর শোনো কাল আমরা বেড়াতে বের হব। ফিরোজা বাচ্চার মতো মাথা দোলায়-- কোথায়? তুমি যেখানে যেতে চাইবে আলম বলে-পার্কে সিনেমায় কিংবা কোনও ভালো হােটেলে খাব।

সত্যি-ফিরোজা জিজ্ঞেস করে। ঘাড় কাত করে আলম-সত্যি, কাল তো হাফ-ডে, আমি সবকিছু ঠিক করে নিয়েছি, নোটন-টােটনকে পাশের বাসায় রেখে বিকেলে আমি আর তুমি যাব। ফিরোজা কতক্ষণ চুপ করে থেকে আস্তে বলে-আমি অনেকদিন বাইরে যাই না, জানি তোমার তো সময় হয় না, তাই তোমাকেও বলি না, কিন্তু মাঝে-মাঝে খুব খারাপ লাগে, সারাদিন শুধু ঘরের মধ্যে, শেষ কবে বেড়াতে গিয়েছি সে তো ভুলেই গেছি. কাল আমরা সত্যি যাচ্ছি। তো? আলম হাসে-সত্যি, তুমি ঠিক করো কোথায় আমরা যাব। ফিরোজা মাথা হেলিয়ে সামান্যক্ষণ ভাবে-ঠিক আছে, আমি ভেবে-চিন্তে তোমাকে বলব। সামান্যক্ষণ চুপচাপ গেল। ফিরোজা হাত ধরে টানে আলমের-চলো। আলম উঠে না-এখানেই থাকি বসে, কী সুন্দর রাত। কিন্তু সে পেছনে ফিরে ফিরোজার চোখের দিকে তাকিয়ে হেসে ফেলে বলে-ও বুঝেছি, চলো চলো।

সকালে রোজাকার মতো ঘুম ভাঙে আলমের। জানালা গলিয়ে রোদ এসেছে মশারির ওপর, ময়লা মশারির একাংশ হলুদাভ উজ্জ্বল। ঘরের ভেতর যে-দু’টাে চড়ুই বাসা বেঁধেছে তারা উড়ে যায়। বিছানার চাদরের এদিক-ওদিক দু-তিনটে ছোট-বড় ফুটাে । আলম সে সব গুণতে গুণতে উঠে পড়ে। কলঘরে ব্রাশ হাতে বসার আগেই সে রান্নাঘরের দরোজার কাছে ফিরোজাকে দেখে । তার পায়ের শব্দে ফিরে তাকিয়ে ফিরোজা হাসে। গতকালের কথা মনে পড়লে আলমও হাসে। অনেকদিন পরে তারা দু'জন-দু’জনকে নতুন করে দেখছে। গতরাতের স্মৃতি বিয়ের ঠিক পরের দিনগুলোর মতো সজীব । অনেক দিন পর ঝগড়াটা হয়েছিল ভাগ্যিস ।

আলম দাঁত মেজে উঠে আবার ব্যস্ত হয়ে যায়। আজ অবশ্য রেশন আনার ঝামেলা নেই। কিন্তু নাস্তা খেয়ে বাজার থেকে ফিরে আসতেই সময় পেরিয়ে যায়। গোসল সারার আগে সে পুরোনো কাপড় আর তেল দিয়ে ঘষে-ঘষে মোটরসাইকেল সাফ-সুতরো করে। পানি দিয়ে চাকা, মাডি-গার্ড এসব ধুয়ে-মুছে নেয়। ইদানীং খুব ফলস্ স্টার্ট নিচ্ছে আর স্পিড বেশি তুললেই স্পার্কিং আরম্ভ হয়ে যাচ্ছে-ওয়ার্কশপের লোকজনও এসব সারাতে পারছে না । গোসল'-টোসল সেরে নোটন-টোটনকে মোটরসাইকেলের পেছনে বসিয়ে স্কুলে নামিয়ে দেয়। আজ হাফ-ডে ।

দুপুরে লাঞ্চের সময় সে নোটন-টােটনকে নিয়ে ফিরে আসে। দুপুরে খাওয়ার পর বাসন-কোসন গুছিয়ে রেখে ফিরোজা আলমের পাশে এসে শোয় । বলে- কোথায় যাব ঠিক করেছি জানো? আলম মাথা নাড়ে-উহু, কোথায়? কোথাও না—ফিরোজা খুব দ্রুত বলে। আলম একটু বোকার মতো তাকালে ফিরোজা বলে কোথাও না মানে আমরা পার্কে যাব না; সিনেমায় যাব না; কিন্তু কী করব জানো, তোমার মোটরসাইকেলের পেছনে চেপে বসে আমি শুধু ঘুরব, শুধু রাস্তায়-রাস্তায় ঘুরব, দেখি তুমি কত দূর আমাকে নিয়ে যেতে পার। আলম খুব সাহসী গলায় বলে-ঠিক হ্যায়, আমি তোমাকে এমন-এমন জায়গায় নিয়ে যাব তুমি খুব অবাক হবে। তা তো হবই-ফিরোজা মাথা দোলায় কতদিন ঘর থেকে বের হই না জানো, এতদিনে কত বদলে গেছে শহর । আলম সামান্য মৃদু গলায় বলে—তা বটে, আমি সব জানি, কিন্তু সময় কোথায় বলো— বাজার, রেশন, নোটন-টোটনদের স্কুল, অফিস করে সারাটা সময় চলে যায়, আসলে আমিও অনকদিন পর বের হব ।

দুপুরাটা গল্প করে কাটে। ফিরোজা আলমের চুল থেকে হাত সরায় না। বিকেলের আগে-আগে উঠে তারা জামা-কাপড় বদলে নেয়। পুরনো ঐট্রাঙ্ক থেকে বের করে ফিরোজা একটা পুরনো শাড়ি পরলে আলম অবাক চোখে তাকিয়ে থাকে- তুমি আসলেই মাৰ্ভেলাস... নোটন দেখ তো, তোমার মাকে কেমন লাগছে? ফিরোজা নোটন-টােটনকে ডেকে বলে— বাবুরা আমরা একটু বাইরে যাচ্ছি, তোমরা দু’জন রঞ্জুদের বাসায় থেকো, ফেরার সময় তোমাদের জন্যে চকলেট নিয়ে আসব।

নোটন-টোটন মাথা নাড়ে। দরোজায় তালা দিয়ে চাবি পকেটে রাখে আলম । নোটন-টােটন রঞ্জুদের বারান্দা থেকে হাত নাড়ে। আলম বলে-ইশ, কতদিন পর আমরা বের হচ্ছি। তোমার কথাই ঠিক ফিরোজা, কোনও নির্দিষ্ট দিকে নয়, যেদিকে চোখ যায়, শুধু সেদিকেই যাব।

বাকিটুকু পেরোতেই সামান্য স্পিড বাড়ায় আলম, ফিরোজাকে বলে-যেদিকে যায় মোটরসাইকেল সেদিকেই আমরা । সামান্য এগিয়েই সে দেখতে পায় রেশন শপ; ফিরোজাকে দেখায়-ওই যে ওখান থেকে রেশন তুলি ... আর ওই যে বাজার, আর কতকটা এগিয়ে সে বাজারের দিকে আঙুল উচিয়ে দেয় এখন তো ভিড় নেই, সকালবেলা দেখলে বুঝতে কী অবস্থা। খুব আমুদে গলায় কথা বলতে-বলতে আলম স্পিড তুলে এগিয়ে যায়। বেশ দূরে নোটনদের স্কুল দেখে সে স্পিড ক্রমশ কমিয়ে আনে। স্কুলের সামনে এসে থেমে যায় হঠাৎ—এটা কি জানো, উহু সাইনবোর্ড দেখলে হবে না, এটা হচ্ছে নোটন-টোটনদের স্কুল। ফিরোজার দেখা শেষ হওয়ার আগেই আলম ইঞ্জিন স্টার্ট দেয় । খুব একটা ভাবছে না আলম, মোটরসাইকেল যেন অনেকটা নিজের ইচ্ছেয় এগিয়ে যাচ্ছে। অফিসের সামনে এসে সে খুব কায়দা করে মোটর-সাইকেল থামায়-এবার বলো আমরা কোথায় এসেছি? ফিরোজা কিশোরীর মতো মাথা দোলায়--কীভাবে বলব বলো, একটু সন্দেহ হচ্ছে বই-কী । ঠিক সন্দেহ-আলম জোরগলায় বলে- ওই যে পশ্চিম দিকে কাচের জানালায় নীল রঙ, ওই ঘরে আমরা বসি। এরপর তারা আরও এগিয়ে যায়। দু’পাশের লোকজন, গাড়িঘোড়া, ভাঙাচোরা রাস্তা। এসবের মধ্যেও আলম খুব স্বচ্ছন্দে মোটরসাইকেল এগিয়ে নেয়। আর এবার দেখ, সে বলে, ওখানে আমি মোটরসাইকেল সারাই, ওই যে, নিবেদিতা ওয়ার্কশপ, চেনাজানা লোক আছে, আলাপ করবে? ফিরোজা বলে-ধ্যাৎ । মোটরসাইকেল আরও এগিয়ে যায় । তোমাকে একটা মজার জিনিস দেখাব--- আলম বলে-ওই যে ডানপাশের একতলা হলুদ বাড়িটা, কে থাকে জানো, ব্যাটা সুদখোর হান্নান, আমাদের সঙ্গেই কাজ করে, আমি দরকার পড়লেই ওর কাছ থেকে টাকা ধার নেই, সুদ নেয় নিক তবু ভালো, আজকাল কে ধার দেয়?

আলমের কাধের ওপর একটা হাত রেখেছে ফিরোজা, আর এক হাতে সিটের একাংশ ধরে ব্যালান্স ঠিক রাখছে। এসব জায়গার কথা প্রায় সে আলমের মুখে শুনেছে। আজই সে প্রথম দেখছে। এবার নিশ্চয় আরও এগিয়ে যাবে তারা, সে ভাবে । আলম দ্রুত স্পিডে দু’পাশ থেকে ক্রমশ এগিয়ে যাচ্ছে। স্পার্কিং আরম্ভ হলে সে স্পিড সামান্য কমিয়ে আনে। আরও কিছুটা এগিয়েই রাস্তাঘাট চেনা-চেনা মনে হয় ফিরোজার। আর একটু এগিয়েই ফিরোজা দেখতে পায় তাদের বাড়ি, রঞ্জদের বারান্দায় নোটনকেও সে হয়তো এক পলক দেখে । তারপরে ক্রমশ তার চোখে পড়ে রেশন শপ, নোংরা ময়লা কাদায় একাকার বাজার । সে আলমকে বলে- তুমি আবার এ-পথে এলে যে বড়, এ-পথে আমরা তো প্রথমেই ঘুরে গেছি। কই-- আলম বলে, তারপরেই সে-ও অবাক হয়— আরে তাই তো, একদম খেয়াল ছিল না। ততক্ষণ তারা নোটন-টােটনদের স্কুল ছাড়িয়ে এসেছে। ফিরোজা ভাবে এবার তারা অন্যদিকে ঘুরবে। আলমকেও খুব নিরুদ্বেগ দেখায়। কিন্তু একটু পরেই ফিরোজার চোখে পড়ে আলমের অফিস, তারপর নিবেদিতা ওয়ার্কশপ, আরও এগিয়ে সুদখোর হান্নানের বাড়ি। ফিরোজা রেগে যায়—কী ইয়ার্কি মারছ, তুমি কি একই রাস্তায় ঘুরাবে আমাকে? দাড়াও ঘুরাচ্ছি, কী যে হল, বেখেয়ালে এক রাস্তায়ই চলে এলাম— আলম মোটর-সাইকেলের ওপর খুব নজর রাখতে রাখতে বলে ।

কিন্তু সামান্য পরেই ফিরোজা প্রায় চেচিয়ে ওঠে। আবার মোটর সাইকেল তাদের বাড়ির সামনে ফিরে এসেছে। তারপর ক্রমশ রেশনশপ পেরিয়ে বাজারের দিকে এগিয়ে যাচ্ছে। ফিরোজা গম্ভীর গলায় বলে- আমাকে নামিয়ে দাও, এসব ঢঙের দরকার নেই, তুমি কি অন্য রাস্তা চেনো না? কিন্তু আলমের কাধে রাখা ফিরোজার হাত টের পায় আলম কাপছে। সে বলে- না না, দাড়াও ফিরোজা, আমি দেখছি। সে মোটর সাইকেলের ওপর ঝুকে পড়ে; তীক্ষু চোখ রাস্তার দিকে তাকায়, বারবার অর্থহীন গিয়ার বদলায় সাইকেলের, স্পিড বাড়িয়ে আবার কমিয়ে আনে। কিন্তু মটরসাইকেল ক্রমশ তাদের নিয়ে বাজার পেরিয়ে আসে, রেশনশপ ছাড়িয়ে আরও এগিয়ে তারা দেখতে পায় নোটন-টােটনদের স্কুল, আলমের অফিস, নিবেদিতা ওয়ার্কশপ । আলম খুব চেষ্টা করে, সাইকেলের কত কী ঘোরায়-নাড়ায়, ফিরোজা তার কিছু বোঝে না, খুব কাঁপছে আলম সে শুধু বুঝতে পারে। আবার তারা ফিরে আসছে ফিরোজা টের পায়। আলমের হাত কেঁপে যায় মোটরসাইকেলে, সে চেচিয়ে উঠে- ফিরোজা আমি চেষ্টা করছি ফিরোজা, কিন্তু বাজার, রেশনশপ, নোটনদের স্কুল, ওয়ার্কশপ, সুদখোর হান্নানের বাড়ি- আমি বের হতে পারছি না, ফিরোজা আমি বের হতে পারছি না।

The Circle

Moinul Ahsan Saber

Translated by Masrufa Ayesha Nusrat

Feroza had slipped out of bed at dawn, carefully lifting one corner of the mosquito net as she did so. Alam recalled her nudging him before she left. It was a pair of sparrows who eventually got him out of bed. Sunlight was streaming into the room through the window, brightening that part of the grimy mosquito net it had fallen upon. Alam shifted his gaze from the sparrows towards the patch of light, staring at it for some time. Both his sons were studying on the veranda. Sitting up in bed, he could see the eldest boy’s head rocking back and forth. Alam stretched, taking his time. These were his only moments of pleasure during the entire day. He wanted to spend this brief interlude as he pleased. There wouldn’t be a minute to spare once he was out of bed. He looked at himself in the small, dull mirror on the wall, turning away before that inevitable pang of disappointment took hold. But a single glance had revealed everything – the dark circles beneath his eyes, sunken cheeks, a torn and grubby undershirt. He smiled to himself as he stood in front of the mirror, looking down at the toothbrush he was putting toothpaste on.

Feroza threw him a glance as she squatted at the tap next to the kitchen. Alam loved her immensely, but ten years of marriage had only exhausted them. He hadn’t been able to give her many of the things a loving husband should. The area around the tap was slippery with mud even in summer. Dark mould had gathered in places. Weeds had grown in the gaps in the cement and the cracks in the peeling plaster. There was a large tree close by; its tough, blackened trunk visible from where she was squatting. Alam rinsed his mouth as he took this all in. By this point, Feroza had made breakfast – wheat rotis with stir-fried vegetables, or some jaggery* and leftovers from the night before, if there were any. A small, old table stood on the veranda, which caught the morning sun at the back of the house. The four of them just about fitted around it. Many things had fallen apart in their household over ten years of poverty, but in all this time Alam hadn’t broken this one rule – Feroza always sat by his side at this hour. A bond grew between them during this short meal, even if momentarily. Feroza could do the impossible. Knowing that they would soon be weighed down by work, she kept everyone amused now. Serving Noton and Toton, she asked Alam, ‘You remember everything you have to do before leaving for work?’ Alam shook his head gravely, ‘I don’t!’ ‘Then listen.’ She counted the tasks off on her fingers: ‘One, go to the bazaar; two, pick up the rations; three, drop Noton and Toton off at school.’ Alam nodded, ‘As you wish, your highness. It shall be done.’ The rations had to be picked up once a week, while the other two were daily chores. But this was how each day began.

The strains of this little pleasure had died by the time he stepped out with the shopping bag. He was reminded of how little he could afford to spend. The bazaar was a stone’s throw away, which was fortunate; otherwise, he would have had to rush to work straight afterwards. A great deal of time was wasted trying to find the lowest prices. He had the desire, but not the means, which infuriated him. He had no choice but to bring home stale, half-rotten food bought cheap. There was no time to catch his breath – putting the shopping bag down, he rushed out again with the ration card and another bag. At the ration store, there would be a long queue of people who also had to go to work. As they waited, they crunched on and spat out inflation, politics, and social degeneration like people eating peanuts. It took a long while for his turn to come. Back home, he bathed quickly; he had 45 minutes to get to work. Long years of habit had accustomed Alam to this routine – he kept pace with the clock and was never late at work. As he hung out his clothes to dry on the veranda after his bath, he could see his children waiting at the table in their school uniform. Alam was used to eating quickly too. Feroza chided him every day, ‘Never mind if you’re a little late, why do you have to eat so fast?’

Serving him some rice, Feroza said, ‘You’re working too hard, look how thin you’ve become.’ At these moments, the realisation that there was so much love beneath the poverty and exhaustion leaped out at Alam. This was the reason Alam loved Feroza so much. Maybe Feroza had spoken without much thought, and what else could she have said anyway? Nevertheless Alam could feel her sincerity. Feroza did not eat with him at this time. She still had too much to do. Her face reddened by the flames on the stove, she would feed Alam, Noton and Toton, see them off, clean the house, finish the cooking, wash the clothes… this was how her day would be spent. Noton and Toton returned home in the afternoon and Alam, just before darkness fell.

Alam had an old motorbike. He had bought it with a loan soon after his marriage. It was still very useful. He had sent it to the workshop for repair the day before yesterday; it often gave him trouble these days. Even if it needed repairs two or three times a month, he was able to do it cheaply because he knew the people at the workshop. He would go to the office after dropping Noton and Toton off at their school. From the street they waved at Feroza as she stood at the door.

Alam hailed a rickshaw. He didn’t usually care for one, but as the motorbike wasn’t an option, and waiting for the bus during rush hour was pointless – Alam decided to get it over with.

Getting off the rickshaw, and paying the fare, Alam paused for a moment.

When the children had disappeared through the school gate, he climbed on to the pavement. With fifteen minutes to spare, he could walk to his office and be in good time.

Not that it mattered even if he were five or ten minutes late. There was no fear of having to provide an explanation. Many of his colleagues were frequently late. Leaving early wasn’t a problem either. But Alam couldn’t do it. Arriving on time had become a strict habit. It wasn’t as though he was bothered by the ethics of it. Nor did he ever consider ringing in sick. He just couldn’t shrug off the habit of punctuality.